The Anatomy of a Villain: Joe Goldberg

"It isn’t hard to convince someone you love them if you know what they want to hear." — YOU, S2.E10 "Love, Actually"

Trigger Warning!

This article contains a detailed discussion of psychological trauma, abuse, stalking, emotional manipulation, mental health issues, domestic violence, and fictional depictions of murder. Reader discretion is advised.

Also contains spoilers!

Disclaimer

This piece does not serve to justify, romanticize, or excuse any of Joe Goldberg’s actions as portrayed in the series YOU. Joe is a dangerous, manipulative, and violent character whose behavior is criminal.

The purpose of this analysis is strictly educational and psychological. It aims to explore how trauma shapes behavior, how distorted narratives can lead to pathological choices, and—most crucially—how audiences may psychologically relate to such characters without endorsing them. This is not a defense. It is a dissection.

Some People Survive Trauma. Others Become It.

Hello, you.

It’s finally the 3rd episode. Reading this, and maybe wondering what kind of person willingly writes about a fictional killer with the precision usually reserved for saints or saints-turned-statistics. Yet, I must tell you that while the blood imprints he leaves behind are his own, the psychological blueprint isn’t. Pieces of it belong to people you know. People you love. Maybe even you. Especially you.

Therefore, this article will begin with a thorough psychological breakdown of Joe’s character, supported by trauma theory, attachment models, and documented syndromes. From there, we will explore the uncomfortable truth of audience identification together: why people see themselves in someone so grotesque.

Because sometimes the monster in the mirror doesn’t just stare back, it understands.

The Psychological Profile of Joe

Joe Goldberg is a system. A system constructed from trauma, filtered through abandonment, and maintained by obsession. Every aspect of his manners (his language, relationships, violence, tenderness) is the rational expression of a damaged psyche struggling to impose order on emotional chaos. To understand Joe is to outline the architecture of that disorder. And this is clinical.

Complex Trauma & C-PTSD

As we all know, Joe’s boyhood is annihilating, not tragic. He was sculpted by lengthy betrayals. His mind is an area of persistent damage, formed by people who were supposed to protect him and instead became the originators of his breakdown. That is the reason why he has complex trauma—a term used in developmental psychology to describe maintained, repeated exposure to harm, neglect, or betrayal at the hands of primary caregivers.

Let’s be specific.

Joe’s father tortured him—burning cigarettes into his arm under the deception of extracting the truth. His mother, emotionally unstable and desperate to escape her own pain, offered no safety. She stepped out with other men, abandoned Joe in public spaces, and ultimately placed him in a group home after he murdered his father to protect her. Instead of seeing this act as the trauma of a child forced into violence, she called him a good boy, rewarded him for killing, and then dumped him.

In psychological terms, this dynamic is textbook parental enmeshment, especially maternal enmeshment. Joe’s mother muddied emotional and moral boundaries by involving him in adult conflicts far beyond his capacity, especially by revealing she possessed a gun and indicating that Joe should one day use it on his father. When he did, she disappeared.

This is how a psyche fractures.

Joe is forced to draw the first moral lines of his life in blood. He learns that protection equals harm, that loyalty justifies murder, and that love will abandon you even when you save it. In his world, there are only three relational roles: savior, traitor, or threat. There is no fourth.

His later placement in a group home did not lessen this damage. There, he was bullied, neglected, and once again made to witness others suffer without being able to interfere. The one adult who showed him kindness—a nurse—disappeared, strengthening his belief that anyone good will ultimately disappear or die. His bond with the nurse only worsened his developing White Knight complex: the desire to rescue women from harm, no matter the cost.

Yes, eventually, Joe finds a paternal figure in Mr. Mooney, a bookstore owner who takes him in. But this is not salvation, it is institutionalized grooming. Mooney locks him in a glass cage for punishment. He rationalizes abuse as discipline, calling it a code to live by. He tells Joe, This is what love looks like. This is what it takes not to become your father.

So Joe learns. He learns that love is a construction—tough, punishing, dark. Pain is a language, control is safety, and cages protect you, even if they hurt.

What results is a textbook manifestation of C-PTSD symptoms: chronic distrust in others, hypervigilance and emotional dysregulation, intrusive re-narration of past events, deep identity disturbance and moral confusion, repetition compulsion: recreating the same wounded relationships with new people, and a distorted belief that violence, if done in the name of love, is moral.

And perhaps the most dangerous of all: a gradual desensitization to suffering. Not because he doesn't feel, but because feeling has been historically punished, ignored, or weaponized.

From a child abandoned with a corpse to an adult who builds cages for lovers, Joe doesn’t change. He simply continues the logic he was taught. Control becomes the answer to love, fantasy becomes the antidote to abandonment, and murder becomes a form of meaning.

This is the profile of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD)—trauma as a developmental condition. Joe is not plagued by a moment, he is shaped by continuity. The child never came out of the fire; he thoroughly learned how to walk through it without flinching.

Disorganized Attachment Style

As you may have noticed already, Joe Goldberg doesn’t love like a stable person. He clings, he fears, he obsesses, he romanticizes partners and then destroys them; he wants intimacy, and yet produces isolation. This is neither an inconsistency nor uncertainty. It’s a psychological attachment style shaped by fear, chaos, and betrayal—a style known in clinical psychology as disorganized attachment.

Let’s define it:

Disorganized attachment develops when a child’s caregiver is both the source of security and terror. The child is biologically wired to seek comfort from the very person who is harming them. This creates a crack in the emotional structure, one that cannot fix itself inherently.

Joe's earliest representatives of attachment are incompatible with stability: his father was violent and emotionally sadistic, using physical abuse as a method of truth extraction, and his mother, who frequently disappeared, was erratic, emotionally immature. When she was present, she placed adult burdens on him, like the implied expectation that he would one day kill his father. Later, when he lived under Mr. Mooney’s roof, affection was conditional, and discipline came in the form of isolated imprisonment in a literal glass cage.

Each of these caregivers destabilized Joe’s core actuality: Love represented fear, affection was unpredictable, and connection was constantly followed by punishment or loss.

From a clinical standpoint, this produces: Attachment anxiety (fear that people will leave, betray, or disappear), attachment avoidance (fear that intimacy will lead to exposure, judgment, or pain), emotional dysregulation (overwhelming feelings that cannot be organized or expressed safely), and hyper-control of relationships (predetermined strategies to prevent abandonment).

This is why Joe stalks, observes people before he speaks to them, gathers information before intimacy, never trusts love as it is, and must edit it to survive. In his mind, people do not come into your life. They are acquired, curated, and managed.

And when love turns real—when it becomes unpredictable, flawed, human—he begins to twist. Every romantic partner he’s had, from Beck to Love to Marienne, eventually triggers the aged fear: they’re going to leave. And when that fear becomes intolerable, his psychological defenses trigger. He narrates, controls, stalks, gaslights, imprisons, or kills.

Unlike how most comprehend, this is not sadism. It’s the expression of a nervous system that never learned safety. Children raised this way desire intimacy, but are also frightened of it. It’s the most disorganized and destructive form of attachment, often linked to personality disorders and violent relational patterns later on in life.

Joe’s relational behavior is the grown-up performance of a child who never learned what secure love feels like. He hurts people because he expects pain from love, and tries to deliver it first, in controlled doses, before it arrives uncontrollably. The tragedy isn’t just that Joe loves badly. It’s that he was never loved in a way that made anything else possible.

Savior Complex & White Knight Syndrome

Joe does not just fall in love—he arrives on a mission, and to be precise, a rescue mission. Each woman is someone he must rescue, fix, and complete. Beck, Love, Marienne—they are all hurt in ways that resemble his mother and the nurse from the group home. Their suffering is the condition for his affection. Their healing, his task.

He is constructing a redemptive arc in which he alone is the hero.

Yet, this pattern is not incidental. It is the hallmark of a Savior Complex, also referred to as White Knight Syndrome—a psychological pattern where an individual is driven to "rescue" others in order to validate their own worth, replay unresolved trauma, or acquire hidden control over emotionally vulnerable people.

In Joe’s case, however, the cost is never frankly his own. What begins as emotional rescue evolves into entitlement, the belief that once he has saved someone, they owe him loyalty, love, and permanence. Let’s elaborate further.

His earliest emotional injury originates from, if I may, powerlessness in the face of suffering. He couldn’t save his mother from abuse. He couldn’t protect the nurse at the group home. He watched others be harmed and could do nothing, and when he finally could, he killed his father. That act, encouraged and morally validated by his mother, established a dangerous belief: love demands sacrifice, protection justifies violence, salvation makes you good.

But his mother’s abandonment immediately after that event corrupted this core belief. So now, when Joe saves someone, he makes sure they stay.

Also, Joe doesn't fall in love with people. Instead, he falls for archetypes. Beck is the misunderstood writer drowning in shallow circles. Joe sees her and thinks: I know you. I will help you become yourself. Love is the emotional wildcard. A mother, a mirror, a murderer. Joe believes she’s the first to truly understand him—until she acts without his permission. Then she becomes a threat. Marienne is the redemption fantasy. A damaged but powerful single mother whom Joe can rescue from addiction, custody battles, and her abusive ex.

These women are tests, each one an unconscious attempt to rewrite the original wound. If I save her, maybe this time she won’t leave. However, real people act unpredictably. They make choices. And when they do, Joe interprets it not as betrayal, not autonomy.

So, the darker side of the savior complex emerges when saving becomes possession. In his logic: if he protects you, you should be devoted; if he understands you, you should love him; if he accepts your past, you should never cross him. When these unspoken contracts are violated, Joe punishes both out of rage and from a deformed sense of moral injury. He believes he was owed gratitude and he did everything right.

His hyper-empathy for women in pain, especially those who resemble his mother, might not seem like a bad thing at first glimpse, but when combined with that desensitization and justification of violence, it meant that in order for him to save these women, he wasn’t afraid to kill. That is the pivot point. He kills to correct the narrative and eliminates obstacles for coherence because in his world, a savior who loses control is no savior at all.

Joe’s White Knight Syndrome is his entire emotional template. He cannot simply care for someone, he must rescue them. Once he does, they must submit to the fantasy he’s written. To reject it is to shatter his meaning, and Joe has always chosen destruction over incoherence.

Obsessive Love Disorder & Erotomania

Joe Goldberg constructs love. Before he even knows a woman’s name, he’s already imagined the conversations, the vulnerability, the synchronicity. She is no longer a person, she is a projection, role, or resolution. The worst part is, he truly believes it. This is not romance. It’s pathology.

Particularly, it aligns with Obsessive Love Disorder (OLD)—a condition marked by an overwhelming fixation with another person, coupled with the inability to accept boundaries, ambiguity, or rejection. In more severe forms, this slips into Erotomania: the delusional belief that someone is already in love with you, or would be, if only the obstacles were removed.

From the moment Joe meets Beck, his fantasy kindles. He narrates her life as if it belongs to him (her apartment is too open, her friends don’t deserve her, her boyfriend is unworthy). She doesn’t choose Joe—Joe chooses her. And because he sees himself as her true partner, everything becomes justified: reading her messages, stealing her phone, eliminating rivals. These are all acts of love in a world too blind to recognize.

This is classic erotomanic logic. In his mind, the relationship already exists, and reality merely needs to catch up. As a result, he doesn’t fall in love with real women. He falls for a version he constructs in his mind.

This construction is meticulous. Joe doesn’t seduce directly. He first studies, collects, adapts, and then mirrors the woman’s interests, speaks her language, performs her fantasy back to her. This is behavioral engineering, also deeply manipulative, because it bypasses consent. The woman is responding to a version of herself performed through him.

And when reality interrupts the fantasy—when Beck, or Love, or Marienne begins to push back—Joe experiences it as a disturbance. He doesn’t grieve the loss of love but reacts as though the entire narrative has been sabotaged. That’s what makes him so dangerous. He requires women to fit into the role he has built. If they contrast, the fantasy collapses, and when fantasy is your only refuge from emptiness, collapse feels like death.

Therefore, Joe maintains the fantasy at all costs. Even if it means eliminating the woman inside it.

Covert Narcissism & Distorted Self-Concept

Joe Goldberg sees himself as the most honest man in the room—a victim of other people’s lies, betrayals, and insignificance. He is not pretentious in the traditional sense; he’s not loud or demanding. His narcissism is subtle, internalized, and intensely self-referential. This is the core of covert narcissism, a variant of narcissistic personality structure where the sense of superiority is not depicted through grandiosity, but through victimhood, moral exceptionalism, and a secret belief in one’s own specialness. Unlike the overt narcissist who controls a stage, the covert narcissist builds a private altar to their misunderstood self.

Joe constructs his self-image through narrative. He doesn’t need everyone to love him, just one person. The right person. The person who gets him. Because once he’s chosen, he believes, everything broken inside will reorganize. But this need to be chosen is conditional: the love must arrive without contradiction. Joe’s partners cannot challenge him, question him, or hold him responsible, because doing so disrupts the fragile myth he lives inside. The myth that he is good, selfless, loyal, and necessary.

This myth is built on the debris of his early years. Joe's mother would tell him that he was a good boy for doing what he did, as he was only protecting her. That early exposure to murder, framed as moral, builds the foundation for future desensitization and justification of violence. Here, Joe is taught that morality is situational, and more importantly, that his own emotional truth is enough to justify anything. He grows up believing that if he feels good or justified, then the act is not wrong—it’s simply misunderstood.

This belief is strengthened again and again. When he kills Beck’s ex, when he eliminates Love’s threats, when he frames murders as protective rather than predatory, he always returns to a single internal theme:

“If you knew what I knew...”

This is textbook distorted self-concept, often found in violent offenders. Joe externalizes all blame, yet internalizes all righteousness. And it also overlaps with malignant self-regard—a belief that misconduct is moral when executed by the right person. It originates from narcissism and defends his belief that he’s the misunderstood hero in his own story.

This delusion is what allows Joe to rationalize horrific actions with chilling calm. When Beck is locked in the cage, confronting him about his crimes, Joe doesn’t explode or deny. He offers her a final story, an attempt to rewrite her reality so that his still makes sense.

That’s what covert narcissism does: it seeks redemption through distortion. It bends truth until the monster looks like a martyr. And Joe, at his core, doesn’t want to be feared. He wants to be forgiven.

Moral Disengagement & Rationalized Violence

Joe kills—but never without a reason. Every act of violence is framed as necessary, protective, or inevitable. He uses empathy as a scalpel, identifying his victims’ worst traits and sculpting them into villains. We first see this in how he frames his killings. Benji is toxic. Peach is intrusive, manipulative, and obsessed. Beck is blind to the truth. Each of these characterizations performs a role: they make Joe’s decisions morally palatable to himself. He doesn’t see a series of murders, yet, he sees a man doing what must be done to protect love from contamination.

Unlike what most people think, this is not a lack of empathy, it is weaponized empathy. He studies his victims, understands their wounds, uses their flaws to build internal cases against them. When he kills, it is often with sorrow, sometimes even with tenderness, but never with doubt. Because he has trained himself to believe love is a justification, not a feeling.

His internal logic is fortified by years of living within fragmented moral systems. This is how moral distortion becomes psychological survival. Joe must believe he is still good because the alternative is unlivable. So when his actions contradict that belief, he doesn’t change his actions. He changes the story. The more he kills, the more he needs to preserve the myth of himself as righteous. That is the tragedy: his morality doesn’t fade, instead, it becomes more sophisticated.

Hence, moral disengagement. A psychological detachment where guilt is omitted by justifying the cause. It is also cognitive dissonance resolved through distortion. By saying, “If you knew what I knew…” he tells us, and himself, that it is not murder. It is loyalty. It is love. If he ever stops justifying it, he will have to face something far worse than guilt, himself.

Dissociation, Hallucination & Identity Fragmentation

By the time Joe becomes “Jonathan Moore,” he is not pretending. He is dissociating. Rhys Montrose—the imagined killer who begins haunting him—is not a hallucination in the cinematic sense. He is a psychic split: Joe’s repressed violence made flesh.

In clinical terms, Joe is no longer simply rationalizing harm, he is splitting from it. His mind, already fractured by trauma, begins externalizing the parts of himself that no longer fit the story. He invents a persona to contain his violence, his ambition, and his guilt. But this is more than a coping mechanism. It is a crisis of identity.

This is what happens when internal conflict exceeds psychic capacity. When the conscious self cannot integrate the things it has done, it begins to compartmentalize reality.

In Joe’s case, this compartmentalization is extreme. After the events of Season 3, he fakes his death, changes his name, moves to a new country, and inserts himself into an entirely new social stratum. On the surface, this appears to be a strategy. But psychologically, it is a fugue state—a dissociative retreat from the accumulated moral weight of his past.

Rhys Montrose, in this framework, is a manifestation of dissociated identity, a construct the psyche develops to contain the unbearable truth. This aligns with symptoms found in Dissociative Identity Disorder presentations, although Joe’s condition is not formally DID. It is closer to what trauma researchers term ego fragmentation: the fracturing of the self into separate emotional and behavioral components that operate autonomously.

Joe confesses to Rhys, debates with him, kills through him, and crucially, he cannot remember the murders until Rhys reveals them. This indicates significant memory discontinuity—a core feature of dissociation. Joe is not pretending he didn't commit these acts; he genuinely cannot conform them with his conscious identity. That identity, the good man, the lover, the misunderstood writer, is so psychologically essential that his system denies any evidence that contradicts it.

And yet, there are moments when the illusion thins. When Rhys is unmasked, Joe begins to crack. The tidy duality collapses. And in its place emerges something far more dangerous: acceptance.

He lets Rhys die so that he doesn’t have to fight the lie anymore. He reabsorbs the darkness, no longer needing to pretend it's someone else. This is the death of denial and the birth of something colder.

This is the final transformation. He jumps from a bridge not to die, but to kill what’s left of the narrative. He rises from the water not as a man who regrets, but as a man who has made peace with the fracture. There is no longer a good Joe and a dark Rhys. There is only Joe, fully unmasked.

This is what identity fragmentation looks like at its end-stage. Coherence at the cost of humanity.

The Mirror Effect

It would be comforting to believe that Joe Goldberg is an alien. That he exists so far beyond the moral boundaries of our world, so pathological, so fundamentally alienated from recognizable humanity that we are, by definition, resistant to what he represents. That his mind, his cruelty, his compulsions belong to a species of corruption entirely apart from our own. But the success of YOU suggests otherwise. Audiences do not simply observe Joe; they identify with him. Not with his actions, but with the precise, internal agencies that make those actions possible.

Joe Goldberg is not charismatic because he is correct. He is charismatic because he is recognizable.

— Long before he is a character on screen, Joe becomes a voice in one’s head. He narrates each moment with such cold transparency, such measured rhythm, that it feels as though he is not only justifying his own behaviour, but translating yours. He moves through metaphors. He reads people like literature. And above all, he intellectualizes pain to such an extent that it ceases to sting. His commentary does not charm because it is unknown; it charms because it is already familiar.

We relate to Joe because we, too, narrate our own lives. Especially those of us who were not raised in strategies. Those who were forced, by instability or harm, to over-analyze the world in order to survive it. Joe’s monologue is the internal dialogue of the sharp, the emotionally substituted, the ones who were too clever for their own good far too early. He does not allow the world to touch him directly, he engages from behind a wall of glass.

And so do we.

— Joe does not love people. He loves projections. Ideals. Archetypes. He adores symbols he can arrange, control, interpret. If you have ever loved someone not for who they were, but for what they stood for in the theatre of your own mind, you understand Joe. If you’ve ever blurred the line between a partner and a myth of salvation, then you weren’t in love.

You were trying to feel whole.

And so was he.

— Joe desires connection, yes, but only on his terms. He fantasizes about being chosen, about being loved in a way that saves every fracture in him. But not about being known. Real intimacy invites inspection. And inspection, inevitably, reveals what is unworthy. So he replaces vulnerability with surveillance, openness with strategy, affection with structure. He allows himself to feel close but never exposed.

— If you have ever wished for love while simultaneously shrinking from it, if you have disassembled intimacy the moment it began to feel real, if you’ve staged distance in the very process of seeking connection, then you know the paradox Joe inhabits.

Joe doesn’t get close. He gets close enough.

So do many of us.

— Joe is thorough. He is obsessive. He is relentless. In a time where attention is scattered and affection is transactional, his fixation masquerades as sincerity. He listens. He remembers. He notices. He looks. He sees.

But this is not love. This is obsession.

And yet, some small part of us longs to be the object of it. The one who is worth the madness. The one whom someone could never look away from, not even when they should. That is the true danger of Joe Goldberg: not what he does, but how dangerously seductive it is to imagine being loved like that, until it is far, far too late.

— At the centre of Joe’s pathology lies hunger. Abandonment. Rejection. Emotional starvation. These are his fundamental ingredients. And while most of us do not become murderers, many of us carry the same structure: longing to be loved, terrified of being left, spinning narratives around the destruction of our inner world just to stay upright.

Joe builds cages because no one ever built him a home.

He obsesses because no one ever held on.

He kills because no one ever taught him how to stay.

And that is the horror of Joe Goldberg: not that he is unlike us, but that he isn’t.

— Strip it all away: the rhetoric, the control, the constructed self. What remains is a terror we all know but rarely admit: the fear of being nobody. That is what we are running from when we build, chase, narrate, pretend. We are terrified that, in the absence of love or structure, the self will collapse. That nothing will remain. So we put on the armor. We call it confidence, clarity, wit, elegance. We wear it for so long that it becomes an identity.

And perhaps that is the most honest thing I can say. That sometimes I don’t know where the armor ends and I begin.

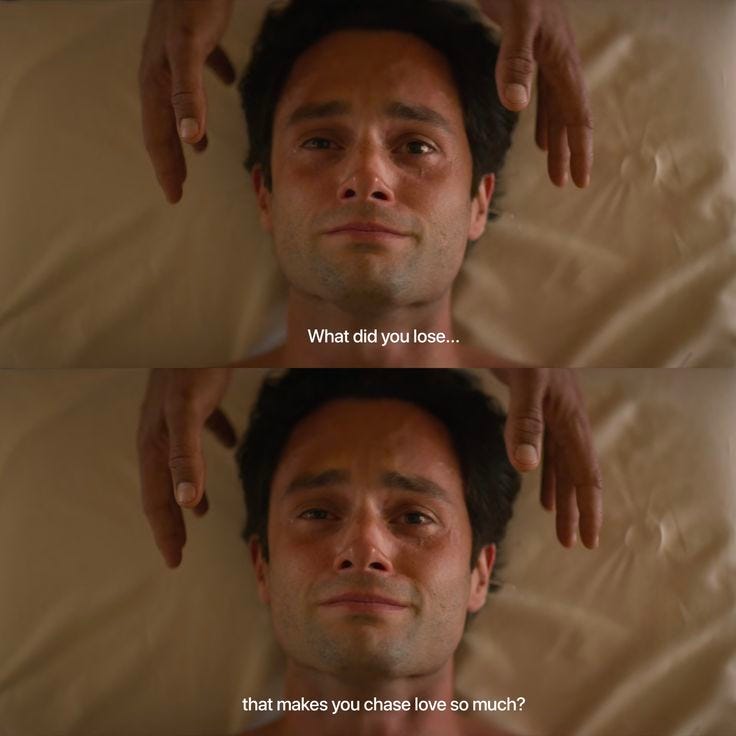

Above, there is one of the best scenes where you can clearly comprehend the way his mind works.

The next villain will be, as request the most in the Hannibal episode, Patrick Bateman from the book and movie called American Psycho.

If you enjoyed this post and wish to show gratitude, you may do so by making a donation starting at just $5 via the link below. Your kindness helps me continue my studies and pursue my profession—thank you.

Thank you for the disclaimer, unfortunate that it's so necessary!

We always need a villian, so we can point our fingers at and say that's the bad guy.