The Anatomy of a Villain: Hannibal Lecter (NBC)

"Must I denounce myself as a monster while you still refuse to see the one growing inside you?" — Hannibal, S2.E9 "Shiizakana"

The charisma of the villain has been a cornerstone of storytelling since time immemorial, as we’ve talked about in the first episode:

Figures like Milton's Lucifer, Shakespeare's Iago, and Shelley's Frankenstein have captivated audiences with their cunning, sophistication, and capacity for destruction. Yet few antagonists have achieved the magnetic pull of Hannibal Lecter, the cannibalistic polymath immortalized in literature and screen. Within the NBC’s adaptation, Hannibal evolves into a figure almost mythopoetic, a philosopher-king of darkness who drives us to question the flimsy boundaries separating good from evil, art from monstrosity. To study his character is to wander through the maze of our own moral ambiguities.

Primal Hunger as Divinity

The Wendigo and the Godhead

In Algonquian folklore, the Wendigo is an insatiable spirit of consumption, a phantom born from human wickedness and the existential void of hunger. Hannibal, in his dual roles as a consummate aesthete and remorseless predator, is a modern representation of this myth. His cannibalism is not just an act of survival but a grotesque greatness, a philosophy wherein to consume is to know, to possess, and to dominate. The stag, recurring throughout the series as a haunting phantom tied to Will Graham’s subconscious, intensifies this duality—a creature of elegance and menace, embodying Hannibal’s simultaneous charm and hazard. The stag’s transformation into the Wendigo mirrors Hannibal’s philosophy: what begins as passion inevitably tops in possession and destruction.

Hannibal’s self-perception develops beyond predatory instinct; he sees himself as an artisan, a creator whose killings ascend to a sacrament. His table becomes an altar, his cuisine a form of worship—not of gods, but of himself, an avatar of primal hunger cleansed by ritual.

Enlightenment Through Corruption

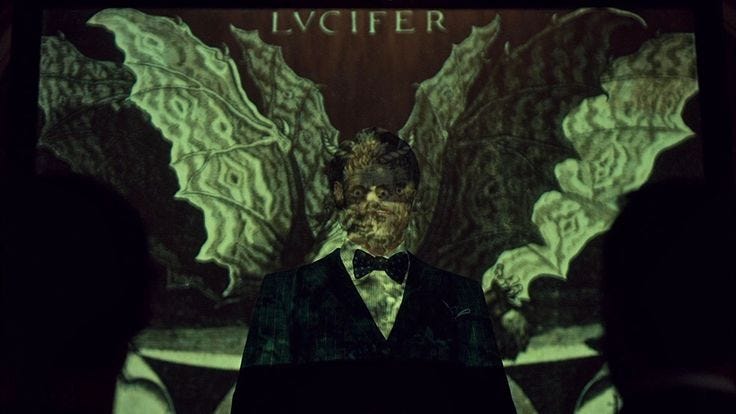

The Luciferian Archetype

Lucifer, in Judeo-Christian mythology, is the fallen angel whose defiance of divine authority symbolizes both hubris and enlightenment. He is a figure who offers forbidden knowledge, embodying the dual roles of corrupter and liberator. Hannibal’s relationship with Will Graham evokes the dynamics of the Fall, not as a punishment but as an awakening. Like Milton’s Lucifer, Hannibal tempts Will to transgress the boundaries of morality, presenting the forbidden fruit of self-knowledge. Hannibal is not merely the serpent but the very tree of knowledge, offering acknowledgments that shatter innocence and impose a godlike awareness of the darkness within. Yet, unlike Lucifer’s rebellion against a cosmic order, Hannibal’s defiance is humanistic, rooted in hate for mediocrity and the cliché of societal norms.

His manipulations elevate him to the role of Metatron—the angelic scribe and voice of God, a divine intermediary—revealing to Will the latent capabilities for violence and appetite that reside in the human psyche. This duality, as both corrupter and illuminator, situates Hannibal in a genealogy of tragic antiheroes who strive for enlightenment, even as their insights corrupt the souls they touch.

Ritual and Reverence

Shintoism and Sacred Aesthetics

Hannibal’s thorough rituals in cooking and killing echo the Shinto reverence for nature and precision. In Shinto philosophy, the sacred is found in nature and ritual. The act of honoring through thorough practice alters the mundane into the divine. The stag, revered in Shinto as a divine messenger, becomes emblematic of Hannibal’s worldview: life and death entwined in a cosmic dance of creation and consumption. Hannibal’s murders are not acts of chaos but manifestations of an order he alone understands—a personal theology wherein beauty sanctifies even the most abhorrent acts.

Consider the precision of his culinary artistry: each dish surpasses its gruesome origins, transforming human flesh into something sublime. This synthesis of horror and artistry underscores Hannibal’s conviction that destruction and creation are inseparable. In this, he mirrors figures from the Japanese tale of Masamune and Muramasa—two swordsmiths whose creations reflect their philosophies. Hannibal’s victims become mediums for his artistry, windows through which he articulates a vision of the sublime.

Hubris

The Icarian Fall

Hannibal’s hubris (excessive pride or self-confidence, (in Greek tragedy) excessive pride towards or defiance of the gods, leading to nemesis) is his fatal flaw, a mirror of the myth of Icarus. His intellect, charisma, and aesthetic sensibilities place him above ordinary men, yet his overconfidence blinds him to the vulnerabilities that exist in his creations. Will Graham, initially a canvas for Hannibal’s manipulations, becomes the sun that melts his waxen wings. Their dynamic, fraught with betrayal and intimacy, displays the tragedy of ambition left lawless by humility.

Like Icarus, Hannibal’s fall is both inevitable and revelatory, a testament to the hazards of striving too far beyond mortal limitations. Yet, his descent does not decrease his brilliance; it immortalizes him as a figure of tragic magnificence, a god undone by his own divine pretensions.

Vengeance as Art

To call Hannibal Lecter a sheer killer is to misunderstand the essence of his being; he is, rather, an artist of the grotesque, a maestro whose medium is human suffering and whose canvas is the lives of his victims. Like Edmond Dantès in The Count of Monte Cristo, Lecter’s acts of vengeance are elaborate and theatrical, yet they exceed simple justice. They are symphonies of suffering composed to reaffirm his intellectual and aesthetic superiority. His choice of victims is never random; each is selected for their insult to his sensibilities or their failure to meet his exacting standards of culture, intelligence, or taste.

Where Dantès seeks to restore moral order, Lecter subverts it. His vengeance is not about balance but mastery. He does not simply punish; he transforms his enemies into objects of beauty—sometimes literal art, as in the case of his tableaux murders. This is vengeance not as a barbaric reprisal but as a sublime act of creation, echoing Nietzsche’s statement that “man must become an artist.”

Nietzschean Transcendence

Hannibal as Übermensch

Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, or Overman, rejects traditional moral rules in favor of self-created values. The Übermensch is an individual who embraces the fullness of life—both its beauty and brutality—to rise above the herd. Hannibal Lecter embodies this concept, topping conventional morality to compose his own values. His disgust for societal norms and his embrace of art, intellect, and power place him in a realm apart, a self-fashioned deity whose existence is an insult to mediocrity. Hannibal’s attempts to mold Will into an Übermensch reflect his own existential journey—a quest to create, in Will, a kindred spirit who can share his aesthetic and philosophical vision.

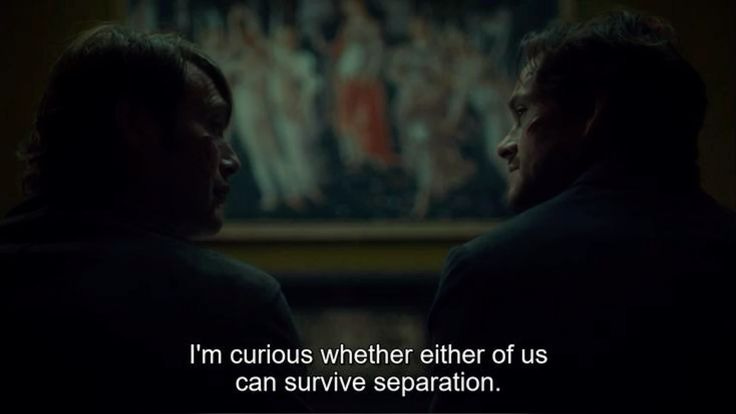

This pursuit, however, reveals the paradox of the Übermensch: in aiming to elevate humanity, Hannibal remains tethered to it, driven by desires and vulnerabilities that betray his godlike aspirations. His fascination with Will is both his greatest strength and his undoing, a reminder that even the most elevated beings are tied by the restrictions of love and obsession.

The Eternal Feast

Fellowship and Betrayal

Hannibal’s dinner parties, macabre reflections of the Last Supper, serve as rituals of fellowship and revelation. His guests, often unconscious participants, participate in meals that blur the lines between creator and destroyer, host and predator. These gatherings display Hannibal’s philosophy: beauty and brutality entwined, the sacred and the profane indistinguishable.

The consummation of this dynamic lies in Hannibal’s relationship with Will, a fellowship fraught with betrayal. Like Judas, Will’s ultimate act of defiance is a betrayal that demonstrates the depth of their connection. In this, Hannibal becomes both Christ and Judas, a figure of sacrifice and treachery whose story reflects the interplay of love and destruction.

The Fire of Revelation

Prometheus

Prometheus, the Titan who gifted fire to humanity, is both a savior and a sufferer. He embodies the paradox of enlightenment—the act of revealing truths that both elevate and destroy. Hannibal embodies this paradox. Like Prometheus, he reveals uncomfortable truths about human nature, peeling back the veneer of civility to expose the primal urges beneath. His psychological manipulations, particularly with Will, are acts of fire-giving, illuminating the darkness within the human soul. But as with Prometheus, Hannibal’s revelations come at great cost, unraveling the lives of those he touches while ensuring his own eventual suffering.

Hannibal’s punishment, however, is self-inflicted. His relentless pursuit of perfection, beauty, and understanding ensures that he will always be isolated, misunderstood, and ultimately betrayed. His Promethean misery lies not in the wrath of gods but in the failures of his own creations.

The Shadow and the Self

Jungian Archetypes

Within the psychological dance between Hannibal Lecter and Will Graham lies a textbook Jungian dynamic. Lecter is the shadow to Will’s ego, the repository of everything repressed and forbidden. Where Will seeks order, Lecter revels in chaos; where Will embodies empathy, Lecter is a model of dispassionate intellect. Yet the two are inevitably drawn together, each serving as the other’s mirror.

Lecter forces Will to confront his own capacity for darkness, suggesting that the line between hunter and hunted is far thinner than one might hope. Their relationship becomes a macabre pas de deux, a struggle not just for survival but for self-knowledge. Each encounter peels back another layer of repression, bringing Will closer to his own shadow and Lecter closer to his ideal companion.

A Catalogue of Vice

The Seven Deadly Sins

Hannibal Lecter’s character can be read as a living epitome of the seven deadly sins, each elevated into a form of art. His gluttony is, of course, literal—his consumption of human flesh transformed into a perverse celebration of gastronomy. His pride is manifest in his intellectual arrogance and hate for those he considers flawed. Wrath drives his elaborate punishments, which are as much about creativity as they are about vengeance.

The remaining sins—lust, envy, greed, and sloth—are less overt but no less significant. His lust takes the form of aesthetic yearning, his envy appears as contempt for mediocrity, his greed manifests in his desire to control, and his sloth is the refusal to engage with a world he deems unworthy. Each sin is not a flaw but an aspect of his identity, explored with meticulous care.

The False Creator

Gnosticism and the Demiurge

In Lecter, one finds the archetype of the Demiurge, the flawed creator of the Gnostic tradition. He constructs entire realities for those around him, bending their perceptions and choices to his will. His god complex is not simply a matter of ego but a fundamental aspect of his identity. Like the Demiurge, he creates imperfect worlds, manipulating others into roles they cannot escape.

Yet, Lecter’s creations are not without purpose. His manipulations often force others to confront truths about themselves, however horrifying. He is both the tormentor and the guide, leading his victims through a process of annihilation and rebirth. In this, he becomes a dark, inverted god—a destroyer who also reveals.

Eros, Agape, Storge, Philia

The Four Biblical Loves

Hannibal Lecter’s relationships withstand simplistic categorization. They encompass all four types of love described in the Bible, each distorted through the lens of his twisted psyche. His eros is expressed in his aestheticism, the sensual pleasure he derives from art, food, and beauty. His agape, or selfless love, is reserved for those he considers worthy, such as Will Graham, whom he seeks to elevate rather than destroy.

Storge, or familial love, is evident in his paternal care for Abigail Hobbs, whom he molds into a reflection of himself. Finally, philia, the love of friendship, appears in his intellectual camaraderie with Bedelia Du Maurier, a relationship built on mutual respect and shared darkness. Each form of love is refracted through the prism of his malevolence, creating a kaleidoscope of connection and corruption.

Hannibal as a Mirror of Humanity

Hannibal Lecter is a tragic muse. Our fascination with him is not embedded in the grotesque spectacle of his crimes, nor in some primal admiration for his monstrous acts. Rather, it stems from something far more unsettling: recognition. The worst in humanity is not found in the unhinged outliers, the "crazy sons of b**ches" whose violence is erratic and mindless. True darkness, the kind that unsettles us most, hides behind charm, intelligence, and refinement. Hannibal is not an anomaly—he is a reflection, a distorted yet eerily familiar visage in the mirror.

The most terrifying villains do not simply horrify us; they seduce us. They do not revel in chaos but sculpt it with precision, turning destruction into an art form. Hannibal’s elegance, his meticulous rituals, his proficiency—these qualities make him something more than a brute killer. He is civilization’s shadow, its most exquisite impulses twisted into something unholy yet beautiful. He displays the unsettling truth that the line between creation and destruction, between beauty and horror, is razor-thin. We are drawn to him because he does not shatter the illusion of control; he perfects it.

When a fox hears a rabbit scream, he comes running—not to help, but to claim what is his. This, perhaps, is the most unsettling reason for our attraction to Hannibal Lecter. He does not consume—he reveals. He exposes the fragility of the moral codes we cling to, the relief with which hunger masquerades as love, how civility itself can be a mask for something primal. In him, we glimpse our own duality, the unspoken knowledge that we, too, are creatures who hunger—not for flesh, but for power, beauty, transcendence. Hannibal, in his dark artistry, gives shape to those unuttered desires, and in doing so, he guarantees that we cannot look away.

In the end, Mads Mikkelsen with his careful, deliberate acting, invites us into the world of Lecter, where beauty and terror are not opposites, but rather two sides of the same coin.

If you enjoyed this post and wish to show gratitude, you may do so by making a donation starting at just $5 via the link below. Your kindness helps me continue my studies and pursue my profession—thank you.

oh my god you don't understand how much i love this!!!! you're such a good writer :)))

such a great analysis! one of my favorite series and most-beloved villains. I am writing a piece on Will Graham at this exact moment so coming across your essay feels whimsically precise