Ex Libris & Cinematica II: The Symposium & Call Me by Your Name (2017)

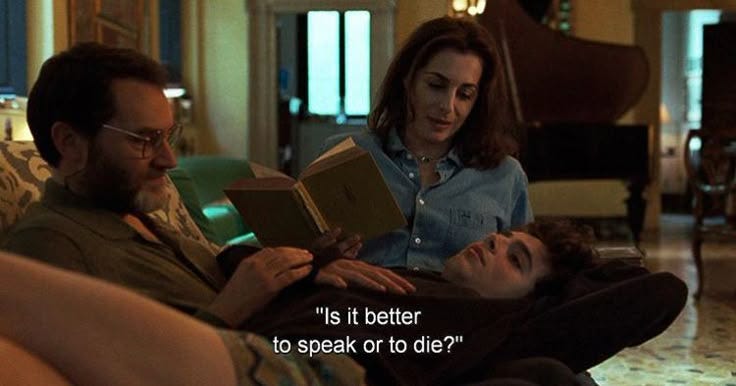

"People who read are hiders. They hide who they are. People who hide don't always like who they are." — Call Me by Your Name (2017)

The Genesis of Desire

In Plato’s Symposium, the figure of Eros is reimagined as a creature of fundamental incompleteness. Diotima1, in her speech to Socrates, narrates a mythic genealogy: Eros is born not of two gods, but of Penia (Poverty) and Poros (Resourcefulness), at the feast of Aphrodite. This parentage is more than an allegorical ornament; it defines the existential state of love itself. Eros is needy, slick, grasping, always in pursuit of something it lacks, never at rest. It is neither mortal nor immortal, but a daimon, a negotiator between the finite and the infinite, between what we are and what we desire to become.

Love, in this framework, is born from a wound, from a crack in the self through which another possibility spreads in. It does not affirm identity so much as it destabilizes it. We love not what we already possess, but what we lack, what we sense vaguely and project outward, onto the beloved as onto a canvas.

This Platonic conception of Eros finds its cinematic counterpart in Call Me by Your Name, where the affair between Elio and Oliver is framed not as an immediate passion but as a slow increase in silence, delays, and emotional tension. Desire accumulates in the gaps between speech and gesture, in the strange tactility of summer heat, in the long afternoons that feel heavy with expectation.

Elio observes him with alternating fascination and disgust, charged with the intensity of someone grappling with his own becoming. Oliver represents a world Elio longs for: confident masculinity, intellectual authority, physical ease, and above all, distance. His Americanness, his casual charm, his unapologetic presence… These mark him as something Elio has not yet become. This gap is the source of Elio’s desire.

The film dwells beautifully in this space of lack. A fleeting touch on the shoulder, a cryptic “Later!”, these small gestures resonate with meaning. Each missed glance, each silence, thickens the ambiance with the ache of anticipation. Here, Platonic Eros comes alive in the tension before fulfillment. Desire becomes a matter of delay, of projection and yearning. As Diotima teaches, it is the art of living with absence.

Elio’s longing is thus philosophical. He craves not just Oliver, but the version of himself that might emerge through this encounter. For Plato, Eros begins with beauty and climbs toward truth, memory, art. Elio’s ache, then, is not merely romantic; it is ontological, rooted in the distance between who he is and who he might yet become.

“He is in between mortal and immortal... and he interprets between gods and men.”

—Diotima, Symposium

The Ladder of Beauty

In her mystifying speech delivered through Socrates, Diotima describes love not as a fixed emotion but as an anamnetic journey, “a gradual ascent of the soul toward the eternal.” The soul, she says, begins by loving one beautiful body. Then, realizing that beauty is not confined to that single instance, it comes to appreciate the beauty in all bodies. From there, it begins to love the beauty of the soul, then the beauty in laws and customs, and eventually the beauty of knowledge, culminating in the direct contemplation of the Form of Beauty: ageless, absolute, and pure.

This is no sheer allegory. It is the architecture of desire as seen through Plato’s eyes. Desire as pedagogy, as the soul’s native impulse toward excellence. Love is not content with possession; it seeks elevation. It is a ladder rather than a loop.

Elio’s love for Oliver, at first glance, appears to be a physical fixation: the obsession with Oliver’s body, his American confidence, his carefree charm. But the film is wise enough to show us that Elio’s desire never rests on the surface. It deepens almost immediately, streaming through shared texts (Heraclitus, Marguerite of Navarre, Celan), music (Bach’s Capriccio, Sufjan Stevens’ “Visions of Gideon”), languages (Greek, Italian, French, body language), and finally time itself.

As their relationship develops, love itself becomes less about gratification and more about cultivation, the cultivation of perception, of memory, of presence. Elio becomes increasingly fitting to beauty in all its expressions: in a gesture, in a fruit, in the sound of a bicycle rolling down a sunlit path. Love no longer belongs solely to the person of Oliver, but shines outward, scenting the landscape, the moment, and the self. This is precisely Diotima’s argument: that love draws us upward, step by step, from the body to the universal.

By the end of the film, Elio has climbed far. And with ascent comes solitude.

The final sequence (Elio sitting by the fireplace, silent, still, eyes glowing with the agony of irreversible experience) is not just the end of a summer romance. It is the summit of the Platonic ladder. Elio has glimpsed something beyond the world of appearance. He has seen beauty, perhaps not the Form itself, but a reflection sharp enough to cut, and he can no longer live in naïveté.

The tears are both out of loss and transformation.

He is not the same boy who watched Oliver arrive that summer day. He is now formed into adulthood, into desire, into absence. His love for Oliver has transfigured him into someone capable of deeper seeing, deeper feeling. In that final moment, his soul, marked now with the imprint of love, has begun its long philosophical journey.

“He who has been educated thus far in the ways of love... will suddenly behold a beauty astonishing in its nature—pure, unmixed, and eternal.”

—Diotima, Symposium

The Divided Self & Longing for Wholeness

In the Symposium, Aristophanes offers a myth as strange as it is tender. Humans, he says, were once spherical beings: complete, with four arms, four legs, and two faces turned in opposite directions. But their wholeness was their downfall. Threatened by their self-sufficiency, the gods split them in two, scattering their halves across the earth. Ever since, love has been the yearning of each half to find its missing counterpart, to touch again the ghost of the original self, and be made whole.

This is an ontological diagnosis. Love, in this view, is about completion. It is the soul’s memory of its own fragmentation and its desire to reverse the violence of that split.

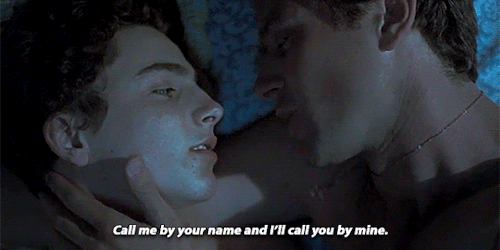

Elio and Oliver are not “halves” in the mythic sense; they are not mirror souls waiting to be perfectly rejoined, but their love endures undeniable traces of this Aristophanic longing. From the very beginning, Elio does not simply desire Oliver. He attempts to assimilate him. He studies him like a text written in a language he already half-understands. He slips into Oliver’s clothes, imitates his vocal rhythms, shadows his characteristics. The line between admiration and identification begins to blur. What Elio craves is Oliver’s actual being.

Oliver, in turn, plays along. Sometimes playfully, sometimes protectively. There is a scene where he places his hand on Elio’s heart and says, “Call me by your name and I’ll call you by mine.” It is perhaps the most Aristophanic moment in the film: a spell of fusion. Not "I love you" but "I am you." In this moment, language itself attempts to switch the ancient separation. Names are changed; identities blurred. Two become one, or try.

Yet, as in all myths of origin, there is an inevitable return to fragmentation. The gods in Aristophanes’ story do not reunite the halves permanently; they allow only a temporary truce. So it is with Elio and Oliver. Their time together is glowing but finite. Love briefly stitches the wound of separation, only for the old stitching to tear open again. The parting at the train station, though quiet, is explosive. Elio is left staring down a world that is again incomplete.

The genius of Call Me by Your Name is its refusal to treat this separation as a failure. There is no bitterness, no accusation. There is only an ache, if I may, a cosmic ache. Because Aristophanes was right: love is not the cure for our incompleteness but the awareness of it. Love does not eliminate absence; it reveals it. It teaches us how to live with it, how to remember our wholeness even as we walk split through the world. And in that remembering, there is dignity.

“Each of us, then, is a 'matching half' of a human whole... and each of us is always seeking the half that matches him.”

—Aristophanes, Symposium

Love as Initiation

In the Symposium, Socrates stands apart both from the celebrants and the very nature of the desire they all attempt to name. Where Phaedrus praises noble sacrifice, Aristophanes tells myths, and Agathon bathes love in lyricism, Socrates sits quiet, sober, possessed of a knowledge that isolates him. When Alcibiades2, drunk and glorious, bursts in to confess his failed seduction of Socrates, it is not a comic interruption, but a disclosure.

Alcibiades tells us that Socrates is impenetrable to his beauty. Not because he is indifferent, but because he sees something beyond it. “He is the only man,” Alcibiades says, “who has made me feel shame.” Socrates is wounded, but wisely so. He has suffered the beauty of the world and gone through it, emerging with a vision no longer connected to the sensual or the immediate. His desire has been purified, sublimated, disciplined. He is, quite literally, a philosopher: a lover of wisdom.

This is the arc Elio too follows, of course, not as a replica of Socrates, but as a soul moving through a kindred transformation.

At the film’s beginning, Elio is brilliant, sensitive, playful, but naive. His desire is immediate, physical, shy, and then bold. He watches Oliver with the critical hunger of someone who has not yet been hurt, who still believes that love can be gathered like a fruit at its ripest moment. But as their relationship unfolds, Elio’s love matures. He begins to perceive that what he wants is not simply Oliver’s touch, but the meaning of that touch, the beauty, the fragility, the ephemerality of it.

When Oliver leaves, the film gives us one of the rarest images in cinema: a young man in silence, alone, processing the mystery of what has happened to him. The camera lingers on his face for nearly four minutes as he stares into the fire. Nothing is said. Because nothing can be said. He is no longer a participant in love. He is now a thinker of it.

Just as Socrates speaks from a deeper wound, so too does Elio carry the impact of his first, great love as a kind of internal growth. He has suffered beauty. He has seen that love, however joyful, must always carry within it the seeds of loss. He now knows what most do not: that to love fully is to allow oneself to be changed, even if—especially if—that love does not last.

There is a particular kind of nobility in those who love this way: vulnerably, intelligently, with eyes open to both the bliss and the eventual silence that follows. Elio, by the end, is a philosopher in the tragic, brilliant sense. Not one who lectures, but one who knows.

“He who loves the beautiful is called a lover because he partakes of it.”

—Socrates, Symposium

Diotima of Mantinea (Greek: Διοτίμα; Latin: Diotīma) is the name or pseudonym of an ancient Greek character in Plato's dialogue Symposium, possibly an actual historical figure, indicated as having lived circa 440 B.C. Her ideas and doctrine of Eros, as reported by the character of Socrates in the dialogue, are the origin of the concept today known as Platonic love.

Alcibiades (Ancient Greek: Ἀλκιβιάδης; c.450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently fell from prominence.

Pinky asking Santa to gift The Brain “the world”, and it’s still isn’t enough, but still, there’s nothing else to do while he’s still alive and living, so might as well after realizing one is living, and beauty is so far beyond the material. It’s so cool, how far back philosophizing about real beauty goes !