The Anatomy of a Villain: Why Are We Attracted to Them?

"In the darkness of every villain’s heart, there lies a longing for acceptance, a desire to be understood." – Unknown

Villains, those shadowy figures who haunt art and literature, exist as a mirror to our darkest instincts, a canvas upon which we project our repressed desires and fears. Unlike the hero, who is often restricted by the unyielding architecture of virtue, the villain functions in a realm ungoverned by morality, liberated from the restrictions of societal expectations. They are complex, magnetic, and often disturbingly human, which makes their temptation irresistible. To understand why we are so charmed by villains, one must delve into the psychological, philosophical, and literary braces of their role in our collective imagination.

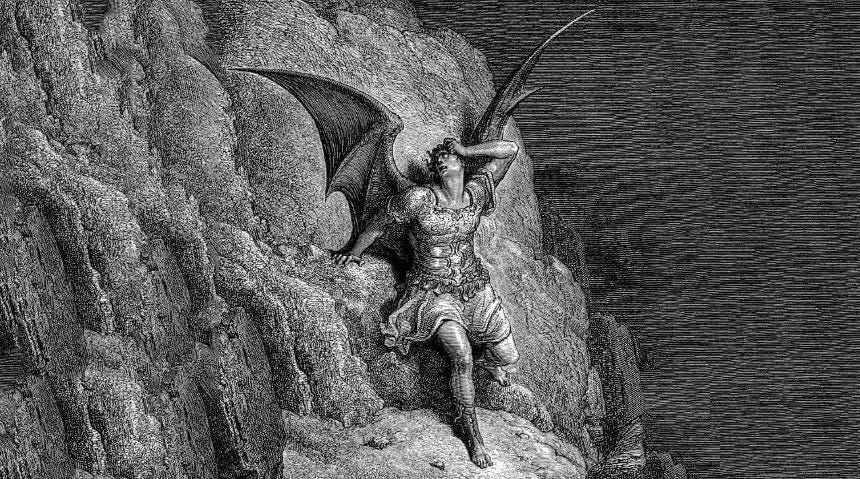

The Villain as the Fallen Angel: Milton’s Satan

Let us begin with the superior archetype of the villain: Satan in John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Milton's Satan is not a mere epitome of evil but a tragic figure, one whose rebellion against divine authority resonates with a deep sense of individuality and defiance. "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven," Satan swears, embodying a spirit of rebellion that is as seductive as it is destructive. His pride, his refusal to bow before what he perceives as tyranny, elevates him to the status of a tragic antihero.

Satan's charm lies in his complexity. He is not wholly evil; rather, he is burdened by a deep sense of injustice and a stubborn passion for freedom. In his soliloquies, we find a character wrestling with his own contradictions: his grandeur and his despair, his ambition and his self-awareness. In this, Satan mirrors the human condition itself, torn between elevated aspirations and inevitable fallibility. He appeals to us because, in his rebellion, we see our own longing to rebel against the forces that tie us—whether they be societal standards, divine orders, or the inevitable march of fate.

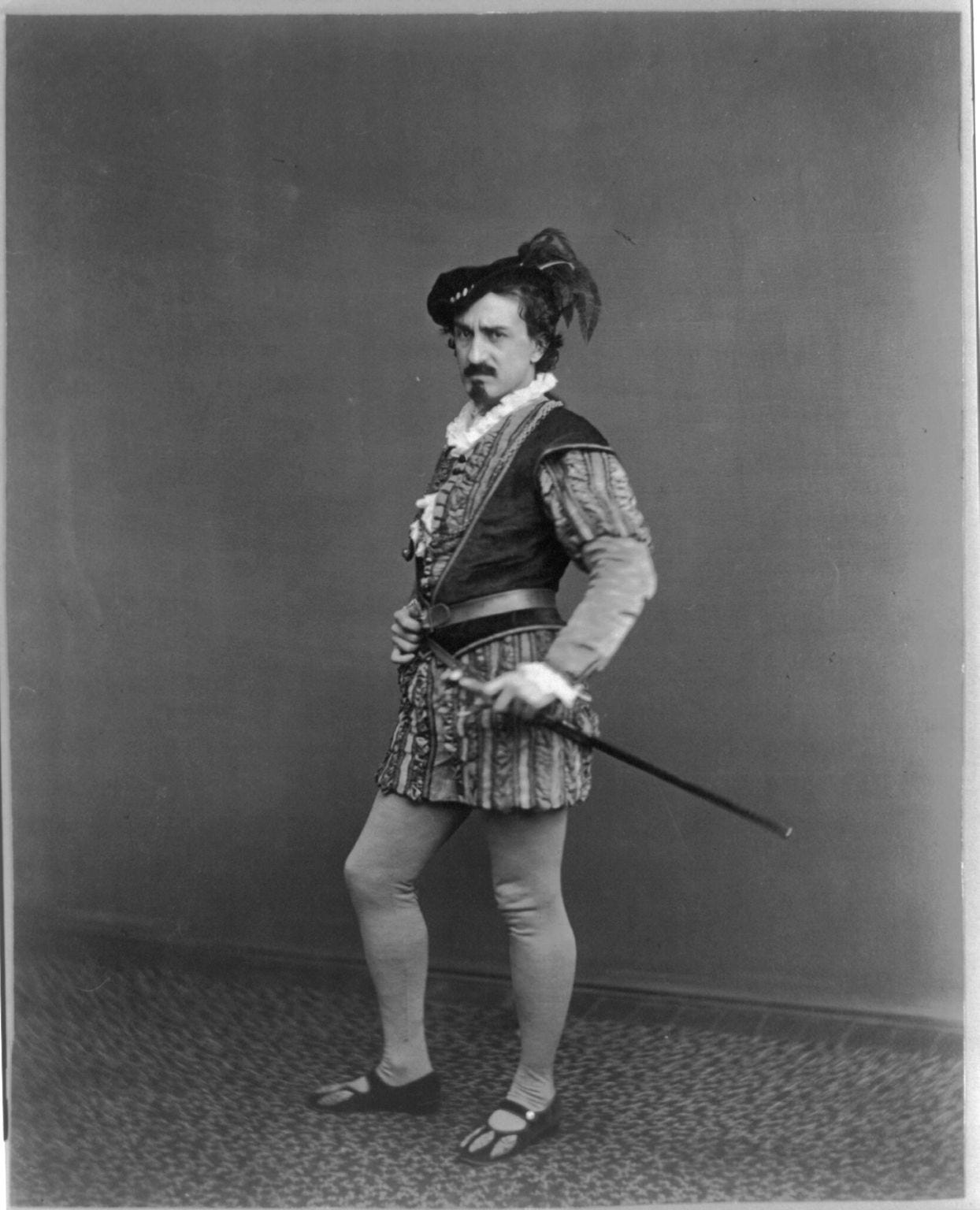

The Allure of the Human Psyche: Shakespeare’s Villains

William Shakespeare’s villains provide a productive ground for exploring the darker cavities of the human psyche. Consider Iago from Othello, a character whose evil is as calculating as it is mysterious. Unlike Milton’s Satan, whose rebellion is magnific and metaphysical, Iago functions on a disturbingly intimate level. His manipulation of Othello and Desdemona is rooted in insignificant jealousy and a cold, almost scientific understanding of human weakness. "I am not what I am," says Iago, a chilling inversion of divine truth that underscores his dishonesty.

Iago’s appeal lies in his intellectual superiority and his proficiency in language. His ability to thread a web of deceit and manipulate those around him is fascinating, even admirable, despite his hostility. Shakespeare grants him no elegant soliloquy to justify his actions, leaving audiences to wrestle with the disturbing possibility that evil can exist without reason. In Iago, we are forced to confront the cliché of evil—the troubling notion that cruelty need not be magnificent or ideological to be effective.

On the other hand, Macbeth, another of Shakespeare’s great villains, offers a contrasting portrayal of villainy. Unlike Iago, whose evil is cold and calculated, Macbeth’s collapse into tyranny is fueled by ambition and existential worry. His soliloquy upon considering Duncan’s murder—“If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly”—reveals a mind tortured by the consequences of his actions. Macbeth is not a villain born but one made, his moral corruption a gradual process that mirrors the vulnerabilities of the human soul. His tragedy lies in his recognition of his own downfall, a recognition that makes him human.

The Villain as the Philosopher: Goethe’s Mephistopheles

Another figure who deserves observation is Mephistopheles, the cunning demon from Goethe’s Faust. Unlike the bare ambition of Macbeth or the cold cunning of Iago, Mephistopheles serves as a philosopher of sorts, personifying cynicism and skepticism in their most refined forms. “I am the spirit that negates,” he claims, a line that suggests his role as both the tempter and the critic.

This time, Mephistopheles appeals to our intellect rather than our emotions. He does not aim for destruction for its own sake; rather, he seeks to reveal the hypocrisies and absurdities of human existence. His relations with Faust—his inquiries, his sarcastic wit—challenge the protagonist’s ideals and, by extension, our own. In this way, Mephistopheles serves as a dark mirror to humanity’s desire for greatness, revealing the moral means and dichotomies inherent in such pursuits.

The Villain as the Tragic Outsider: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Turning to modern literature, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein presents a villain whose tragedy lies in his otherness. The creature, rejected by his own creator and society alike, becomes a villain not by nature but by occasion. His decline into violence is not born of natural hatred but of a desperate need for recognition and love.

The creature’s eloquence and intelligence, if that makes sense, make his difficulty all the more heartbreaking. “I am malicious because I am miserable,” could be the perfect instance of a line that seizes the essence of his tragedy. He is both the victim and the perpetrator, a figure who forces us to question the boundaries between good and evil. In sympathizing with the creature, we are pushed to face the ways in which society creates its own monsters.

The Villain as a Psychological Mirror: Jung’s Shadow Archetype

The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung provides us with a useful framework for understanding the universal charm of villains. According to Jung, the Shadow represents the unconscious aspects of the self— desires, instincts, and traits we suppress or deny. Villains, in this sense, serve as projections of our collective Shadow, externalizing the darker aspects of human nature.

Take, for instance, Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. Although not a traditional villain, Raskolnikov’s act of murder and his following rationalizations mirror the darker motivations that live within us all. His philosophical musings on the nature of morality and the rights of the extraordinary individual force readers to confront their own ethical boundaries. In engaging with such characters, we perform a kind of psychological self-examination, confronting the parts of ourselves that we might prefer to ignore…

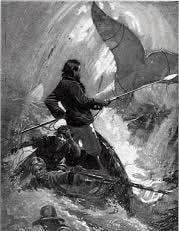

The Villain as a Necessary “Equilibrium”

Beyond their psychological and philosophical dimensions, villains play an essential role in narratives. Without the villain, there can be no hero; without conflict, there can be no resolution. This dynamic is perhaps best epitomized in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, where Captain Ahab’s obsessive pursuit of the supposed whale transforms him into a kind of villain. Ahab’s “monomaniacal” quest is both his greatest strength and his hamartia, or fatal flaw, a force that drives the narrative forward even as it leads to his destruction.

Similarly, in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Kurtz serves as both the antagonist and the manifestation of the novel’s central themes. His collapse into madness and moral vice is not merely a personal tragedy but a critique of imperialism and the corrupting influence of power. In Kurtz, we find a villain who is both a product and a critique of his environment, a figure who forces us to confront the more comprehensive societal forces that shape human behavior.

The Eternal Existence of the Villain

And so, we return to the villain, that dark architect of chaos, not as a mere figure of hatred but as a necessary force in the grand narrative of existence. They stand at the ridge of morality, daring to shout where others stutter, embodying the tension between order and anarchy, virtue and vice. We are drawn to them not despite their darkness but because of it; they shine with a seductive brilliance that heroes, bound by their predictable fairness, can never achieve.

They remind us that life itself is a battlefield of contradictions. To gaze upon the villain is to confront the abyss within ourselves—a confrontation that is as intoxicating as it is terrifying. Villains whisper to us of forbidden freedoms, of lawless ambition, of power. They show us what we might become if only we dared, if only we surrendered to our most primal instincts, if only we reached beyond the oppressive cage of decorum.

Yet, it is not their triumphs or their inevitable falls that captivate us, but their essence: they are us, stripped of hypocrisy, unmasked and raw. In their shadow, we find transparency; in their downfall, we find the reflection of our fragile humanity.

The villain endures as a question to be considered: What are we capable of, when the mask of civility is stripped away? The answer is unsettling, perhaps even unspeakable. And yet, we cannot look away. We never will. For in their darkness, we glimpse something timeless, something eternal—the truth of what it means to be human, bound by the infinite, inevitable shadow of the soul.

If you enjoyed this post and wish to show gratitude, you may do so by making a donation starting at just $5 via the link below. Your kindness helps me continue my studies and pursue my profession—thank you.

Thanks, this was really educational -coming from a music & software degree background

Yes, the villain is us. Our other side, if our reflection in the mirror could show our true nature. We are attracted to the villain because we are attracted to ourselves.

Thanks Dilay for another contemplative piece.