On Objective vs. Subjective Reality: The Collapse of Truth in the Modern Age

A big thanks to this article's muse: @emmanelson

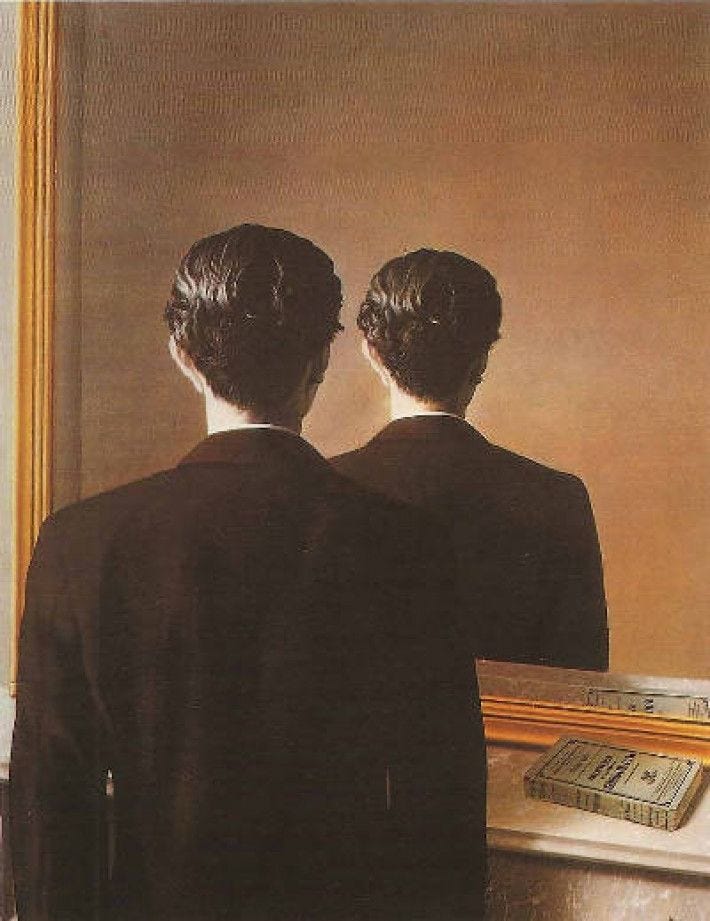

The debate over the nature of reality has been with us since the first glimmers of human thought, and yet it seems that we moderns—so assured of our sophistication—have become lost in a hall of mirrors, unable to distinguish reflection from substance. I speak, of course, of the perennial conflict between objective and subjective reality, a distinction that has shaped human thought for centuries, only to collapse under the weight of our own intellectual excesses. Today, in this modern age of fragments, of illusions and simulacra, we face the consequences of this collapse. But to understand where we are, we must first understand how we arrived here.

The Primacy of Objective Reality: The Greeks, Romans and Beyond

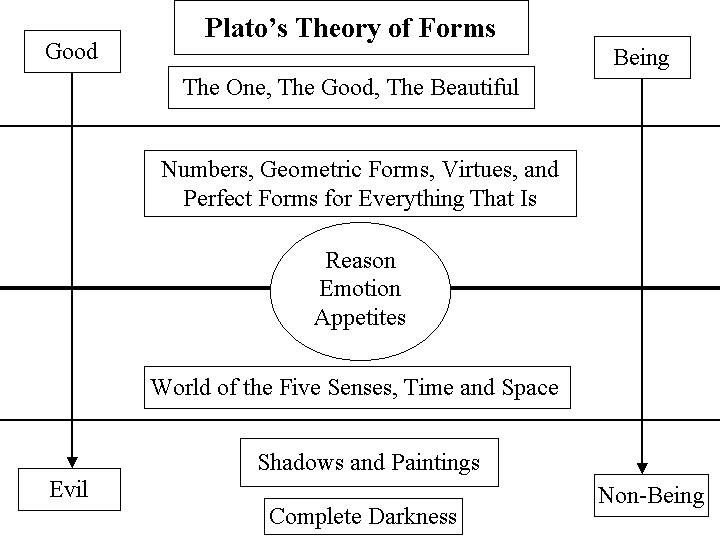

It is fashionable in our era of epistemic uncertainty to deride the ancients for their supposed naiveté. But I find in them a wisdom that transcends the ages. Consider, for instance, the Greeks—the cradle of Western philosophy, a society that sought to uncover the immutable truths of existence. Plato, with his grand metaphysical schema, envisioned a realm of perfect Forms, untainted by the imperfections of the material world. To him, what we perceive with our senses is mere shadow-play on the walls of a cave, illusions that distract us from the real, eternal truths that lie beyond our limited perception.

Plato’s theory of the Forms, while perhaps quaint to the contemporary mind, was nothing less than a profound attempt to reconcile human subjectivity with an objective, unchanging reality. The Forms represented an ideal, existing beyond the caprices of human perception, independent of the individual. The task of the philosopher, Plato believed, was to rise above the deceptive world of appearances and grasp the eternal truths with the mind’s eye—a task that required transcending one’s subjective biases, emotions, and senses.

Aristotle, Plato’s most famous pupil, took a more empirical route, though he too sought to uncover objective truths. His system of classification, his development of logic, his exploration of natural phenomena—these were all part of a grander project to reveal the underlying order of the cosmos, an order that existed independent of human thought. For Aristotle, knowledge was not merely subjective interpretation but the process of aligning the mind with the natural world, of discovering the universal laws that govern existence.

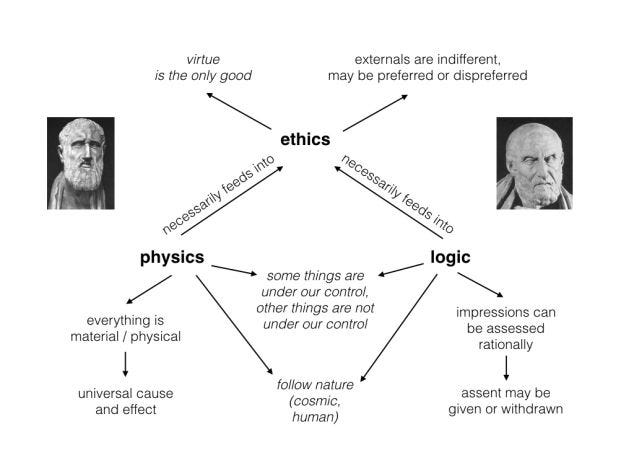

In these early philosophical endeavors, we see the primacy of objective reality—the belief that truth exists beyond the self and that it can be discovered through reason, logic, and observation. To live well, according to the Greeks, was to conform oneself to this higher reality, to order one’s soul in harmony with the cosmos. And yet, the subjective, personal dimension of existence was not entirely neglected. The Stoics, for instance, placed great emphasis on the individual’s internal response to external events. But even here, the goal was to align one’s subjective experience with the objective reality of nature.

The Enlightenment’s Objective Ambition

This belief in the existence of an external, objective reality reached its zenith during the Enlightenment. The thinkers of this era—Locke, Descartes, Newton—believed, with a confidence that now seems almost quaint, that human reason was capable of unlocking the mysteries of the universe. The mechanistic worldview that emerged during this period was both exhilarating and terrifying. It reduced the universe to a series of laws, principles, and equations—cold, rational, and objective. Newton’s laws of motion, for example, seemed to reveal a cosmos that functioned like a great machine, every part moving in predictable relation to every other. Reality, it seemed, could be known, understood, and controlled.

John Locke, the great empiricist, argued that all knowledge comes from sensory experience and that the mind is a tabula rasa—a blank slate—upon which the external world impresses itself. This was a deeply objective vision of reality, one in which truth existed outside the self, waiting to be discovered through careful observation and rational inquiry. Descartes, despite his flirtation with radical doubt, ultimately reaffirmed this vision by grounding knowledge in the certainty of reason. His cogito ergo sum may have been a subjective starting point, but it was ultimately a bridge to the objective, a way of securing the foundations of knowledge beyond the shifting sands of personal experience.

And yet, even during this period of triumphant objectivity, cracks were beginning to appear in the edifice. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason was the first major blow to the Enlightenment’s project of objective knowledge. Kant argued that while there may be an objective reality—the noumenal world—we can never know it directly. Our knowledge is always mediated by the categories of our own minds, the subjective structures that shape how we perceive the world. The objective world, in other words, is always filtered through the lens of human perception, and thus can never be known in its pure form. This was a radical departure from the Enlightenment’s confidence in objective truth and laid the groundwork for the later subjectivist turn in philosophy.

The Subjective Turn: Romanticism, Idealism, and Existentialism

The rise of Romanticism in the late 18th century brought with it a full-scale rebellion against the cold, mechanistic view of the universe that had dominated the Enlightenment. For the Romantics, truth was not something external and objective, to be discovered through reason and observation. It was something internal, something personal, to be felt, experienced, and expressed. Rousseau, Goethe, Wordsworth—all of these men emphasized the importance of individual experience, of emotion, of the inner life. The world, they claimed, was not a machine but a living, breathing organism, and human beings were not passive observers but active participants in the creation of reality.

This shift from the objective to the subjective found its philosophical counterpart in German Idealism, particularly in the work of Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel. For these thinkers, reality was not something that existed independently of the mind, but something that was shaped and constructed by the mind. Hegel, in particular, saw reality as a dialectical process, a constant unfolding of contradictions and resolutions. For him, the objective and the subjective were not two separate realms, but two moments in the same process of becoming. The world, he argued, is not static but dynamic, and it is through this dialectical movement that reality is brought into being.

By the 20th century, the shift toward subjectivity had reached its full expression in the existentialist philosophies of Sartre, Heidegger, and Camus. These thinkers rejected the very notion of objective reality, arguing that existence itself is inherently subjective. Sartre’s famous dictum, "Existence precedes essence," encapsulates this view. There is no preordained reality, no objective truth waiting to be discovered. We are thrown into the world, free to create our own meanings, our own realities, through our choices and actions. In the existentialist worldview, the subjective becomes the foundation of reality, and the individual’s experience is the ultimate arbiter of truth.

The Postmodern Collapse: The Death of Objective Reality

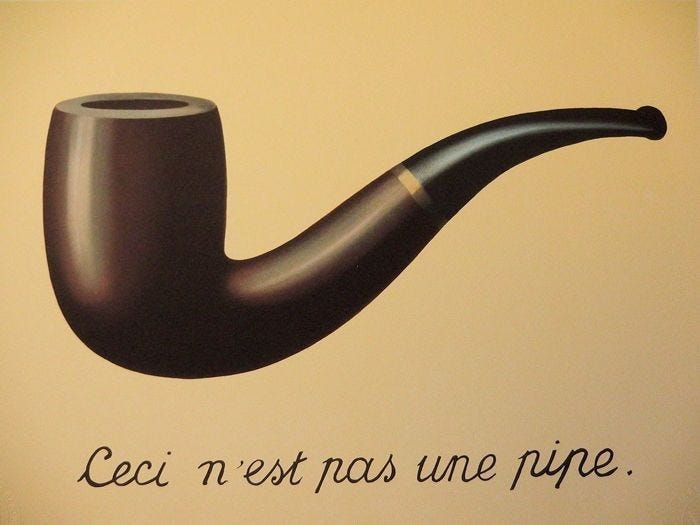

And then, as if in a final act of intellectual self-destruction, the 20th century saw the rise of postmodernism, a movement that rejected not only objective reality but the very possibility of truth itself. Figures like Foucault, Derrida, and Baudrillard dismantled the grand narratives that had sustained Western thought for centuries, leaving in their wake a fragmented, disoriented intellectual landscape. Foucault’s critique of power and knowledge revealed that what we call "truth" is often little more than a construct, a tool used by those in power to maintain control. Derrida’s deconstructionist project showed that meaning is always deferred, always slipping away, never fixed or certain. Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality exposed the degree to which our world has become a simulation, a series of signs and symbols that bear no relation to any underlying reality.

What is particularly insidious about postmodernism is that it does not merely challenge our ability to know objective reality—it questions whether such a thing even exists. If all knowledge is a social construct, if all truths are contingent, then what are we left with? We are left, I fear, with nothing but competing narratives, each claiming to represent reality, none of them capable of achieving dominance.

The Modern Dilemma: Living in the Void

And so, we arrive at the present, in a world where the very notion of objective reality has been hollowed out, replaced by a proliferation of subjective interpretations. We are bombarded by information, by images, by stories, each of which claims to represent the truth. But these truths are fleeting, unstable, and ultimately unsatisfying. The rise of social media, of algorithmic personalization, has only exacerbated this problem, creating echo chambers where individuals are fed only the information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs, further fragmenting our shared sense of reality.

In this landscape, the tension between objective and subjective reality has reached a breaking point. We live in a world where scientific facts are dismissed as mere opinions, where history is rewritten by those who wield the most influence, where reality itself seems to shift and change with every passing day. And yet, we cannot live without some sense of the objective, some belief in a reality that transcends our individual experiences. Without it, we are left adrift in a sea of subjectivity, where nothing can be known, and everything is possible.

But what does it mean to live in such a world? What does it mean to live in a world where the very foundations of reality are constantly in question? Inevitably, it leads to a kind of existential void. The individual in the modern age no longer inhabits a fixed, predetermined world like Newton’s mechanical universe. Instead, we live in a space where everything is fluid, where everything can be questioned, reinterpreted, and reshaped. In such a world, the search for solid ground becomes a desperate pursuit. But is there such a foundation left to be found?

In this state of uncertainty, the individual faces two paths. The first is a retreat into nihilism, where the collapse of objective reality leads to a belief that nothing holds meaning. Without a shared reality, without truths that transcend our subjective experience, some find themselves concluding that life itself is meaningless. This is the dangerous seduction of nihilism, a philosophy that preys on the weakened state of the modern mind, already overburdened by ambiguity and contradiction.

Nihilism, of course, is not a new phenomenon. It is the dark undercurrent of Western thought, surfacing time and again throughout history in moments of crisis. Nietzsche famously declared the death of God, and with Him, the collapse of the entire metaphysical structure that had supported Western civilization for millennia. In Nietzsche’s diagnosis, this collapse was not just religious but epistemic; with the fall of Christian morality came the fall of objective truth itself. In the wake of this collapse, nihilism loomed, threatening to reduce all values, all truths, to mere human constructs, empty of meaning.

But nihilism, though seductive, is not the only path. There is another possibility, one that, while fraught with difficulty, offers a way forward. This second path is the embrace of creative subjectivity—not as a rejection of reality, but as a recognition of the power we possess to shape it. In this sense, we might borrow from the existentialists, particularly Sartre, who argued that while reality may not offer us preordained meanings, we are free—indeed, condemned—to create them for ourselves. If objective truth is unreachable, then the subjective must take on a new weight, a new responsibility. We must become the architects of our own meaning.

In this creative response, the individual does not retreat from the world but engages with it in a new way. Reality becomes a canvas, not a given. We shape it through our actions, our choices, our beliefs. The problem, however, is that this path requires a kind of intellectual and moral courage that many find difficult to master. It requires the willingness to live with ambiguity, to accept the fluidity of truth while still striving for meaning within it. It demands that we take responsibility for the realities we create, rather than seeking comfort in pre-existing certainties.

In the modern age, this has manifested in a variety of ways—most notably in the rise of identity politics, where subjective experience becomes the primary lens through which reality is understood. Individuals now define their realities not through an appeal to shared objective truths but through the assertion of their personal, lived experiences. There is power in this, to be sure. But there is also danger, for when subjective experience becomes the sole arbiter of truth, we risk descending into solipsism—a world in which every individual inhabits their own private reality, disconnected from the larger whole.

And here we see the great paradox of our age. On the one hand, we live in a time where objective reality has never been more accessible—scientific knowledge, technological advancement, and empirical data flood our lives. And yet, at the same time, we are more fragmented, more divided, more uncertain of the nature of reality than ever before. It is a strange irony that in an era defined by information, we struggle to find common ground on even the most basic of truths.

The impact of this shift on the modern world cannot be overstated. The political and social consequences are already apparent, as we witness the rise of populism, the spread of misinformation, and the erosion of public trust in institutions. When reality becomes a matter of personal belief, when facts are reduced to opinions, the very fabric of society begins to unravel. Without a shared reality, democracy itself is in jeopardy, for how can we engage in meaningful discourse when we no longer agree on the terms of that discourse? How can we govern ourselves when we cannot even agree on what is real?

This is the crisis of the modern age—a crisis not merely of politics or culture but of reality itself. We find ourselves standing on the edge of a precipice, looking into the void where objective truth once stood. And the question that confronts us now is whether we will succumb to the darkness of nihilism, or whether we will find within ourselves the strength to forge new meanings, new realities, in the face of uncertainty.

In the end, the tension between objective and subjective reality is not something that can be resolved. It is the central dilemma of the human condition, a tension that has shaped the trajectory of Western thought for millennia. From Plato to Kant, from Nietzsche to Baudrillard, philosophers have wrestled with this divide, each generation seeking new answers, only to find that the questions remain. Perhaps there is a kind of beauty in this perpetual struggle, a beauty that lies in the very impossibility of resolution. For it is in this tension, this dialectic between the objective and the subjective, that we find the essence of human existence—a search for truth that is both eternal and elusive.

In the modern world, we are perhaps more aware than ever of the fragility of this search. But in that fragility, there is also an opportunity—a chance to reclaim the creative power of subjectivity, to forge new paths of meaning in the void left by the collapse of objective certainty. The challenge, as it always has been, is to do so without losing ourselves in the chaos, and to navigate the fluidity of modern reality without falling into despair. It is a daunting task, but perhaps it is the only task that truly matters.

And so, we return to where we began, standing on the precipice, gazing into the unknown. Objective or subjective—these are not merely philosophical categories but the very forces that shape our world, our minds, our souls. To live in this tension is to live with the full weight of human freedom and the terrifying responsibility it entails. But perhaps, in the end, this is the only way to live authentically—to embrace the ambiguity, and the uncertainty, and, in doing so, to find meaning where none was given.

I feel like I just drank from a fire hydrant - but in the best way. So much to sit with and consider here.

You girls sing from my same fucking songs 🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷🩷