How to Lose Like a Master, Vagabond

“I was looking for strength... but I didn’t even know what strength meant.” — Miyamoto Musashi

Contains spoilers!

At first glance, Vagabond appears to be a familiar type of story, what scholars would call a Bildungsroman, a coming-of-age tale. It appears that it might be about a man becoming a significant warrior, a rags-to-riches journey where the goal is martial perfection, glory, and invincibility. But Takehiko Inoue, the creator of Vagabond, denies this formula almost immediately. He does not write a story about a man learning to fight. He writes a legend about a human learning to exist.

The protagonist, who begins as the young, wild, and angry Shinmen Takezō, believes that if he becomes strong enough, if he defeats enough opponents, kills enough men, sharpens his blade sufficiently, he will finally become someone of value. He fights both to survive and to matter. And yet, after every victory, he grows more hollow. The stronger he becomes, the more lost he feels. Why?

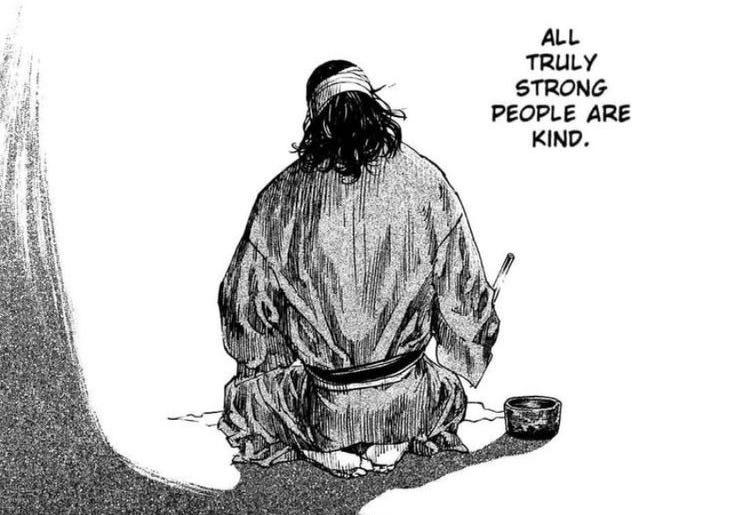

Because strength, as Inoue presents it, is not what the world has taught Takezō to believe. It is not about killing without hesitation. It is not about standing alone atop a mountain of corpses. It is not even about being the best. Strength, honest strength, is internal. It has nothing to do with skill, and everything to do with clarity. This is foreshadowed in real historical documents, like Musashi’s own Dokkōdō (“The Way of Walking Alone”), which he wrote just days before his death. In it, he suggests:

“Do not seek pleasure for its own sake. Do not let yourself be guided by the feeling of lust or love. Do not pursue the taste of good food. Do not hold on to possessions you no longer need. Do not act following customary beliefs.”

All of this reveals a lone vision of mastery: releasing.

What Mastery Isn’t

Musashi’s journey disassembles the specific idea that mastery comes from accumulating more: more techniques, more power, more fame. In the early stages, he fights in the way most people think mastery works, with brute force and willpower. He wins many duels, but he is afraid. His heart remains tangled in fear of weakness, of failure, of being forgotten.

Take his fight with Inshun, the second spear of Hōzōin Temple. Inshun is a child, young, delicate, monkish, and yet he devastates Musashi. Why? Because Inshun has let go of fear. He fights with total presence, almost playfully, like he’s dancing with death. He’s free. Musashi, on the other hand, is burdened by his desire to win, his concern about what losing would mean.

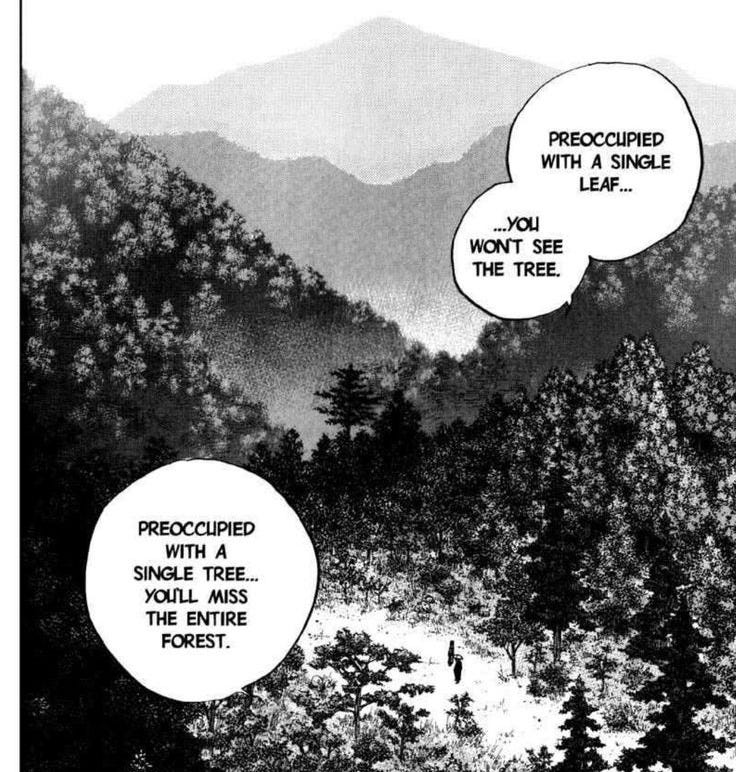

This is where Vagabond makes its central philosophical move: True mastery is not the perfection of technique, but the elimination of what blocks the self from seeing clearly. In Zen Buddhism, there is a saying: “When the archer shoots for no particular prize, he has all his skill. When he shoots to win, he loses.”

The moment Musashi lets go of winning, he begins to see the essence of combat as reflection.

What Mastery Is

After his loss, Musashi does not go off to practice new sword forms or invent a unique technique as expected from him. Instead, he withdraws from the world, physically and spiritually. He disappears into the mountains to confront his own fear. He asks questions, but this time about his self, not about his sword. This is admirably radical. In most stories, the hero trains to become more substantial. Here, the hero pauses to become still.

This is a very Eastern, and particularly Zen-Buddhist, idea of mastery.

As most people would know, in Zen, mastery is not something you obtain. Rather, it’s something you return to by stripping away the ego, the part of yourself that clings to reputation, fear, and comparison. You ultimately realize that greatness was always concealed by your illusions.

Zen kōans, paradoxical riddles used to trigger enlightenment, illustrate this mindset. Here, one famous kōan asks:

“What is your original face before your parents were born?”

You may be confused even after reading it a few times. However, it’s not meant to be answered logically. It’s meant to shatter the illusion that the self is a stable, knowable thing. Musashi’s path mirrors this kind of attack. The more he fights, the more he realizes he doesn’t know who he is, and that realization becomes his first true insight. Let me put it this way:

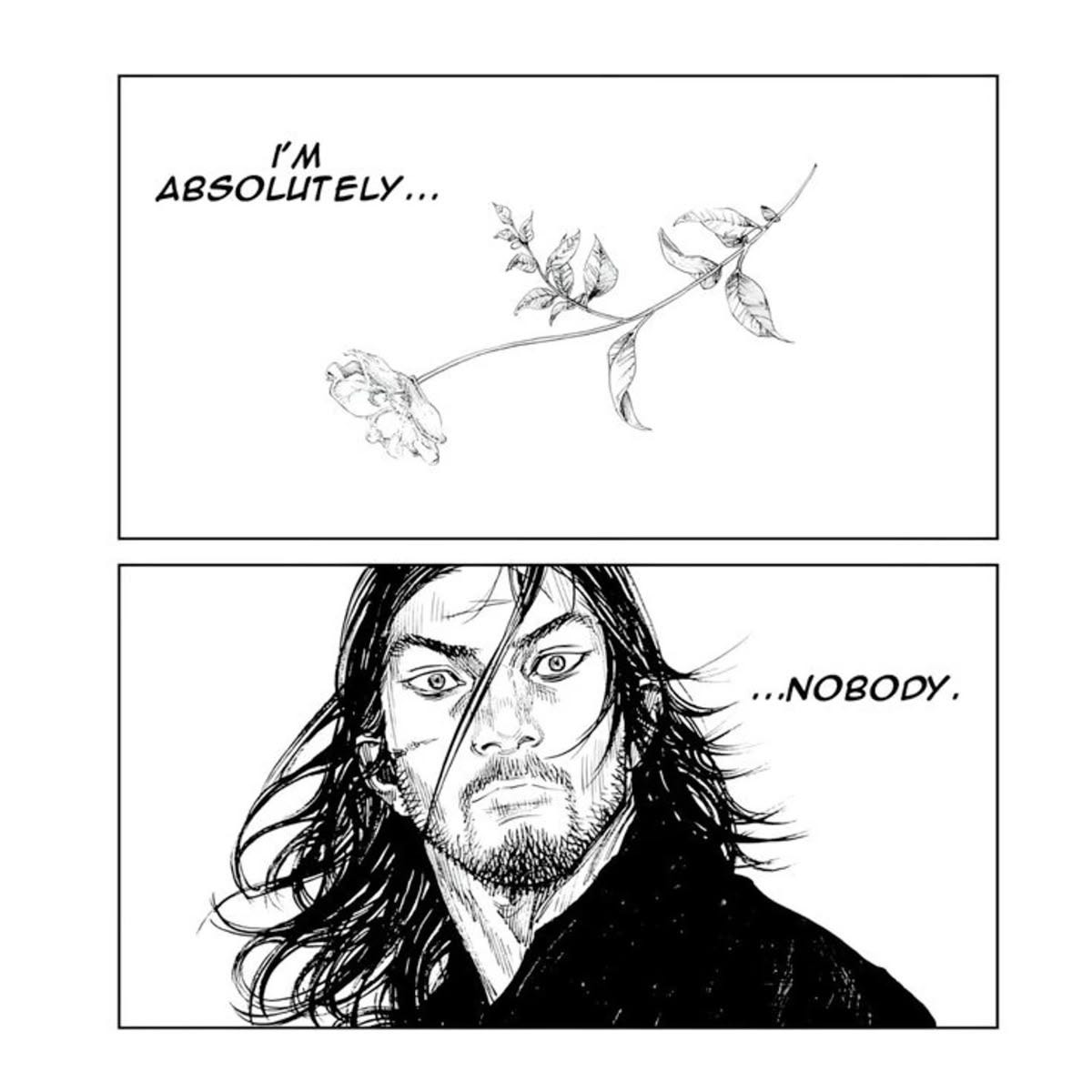

In the Western tradition, mastery is often presented as the peak, the top of the mountain. In Vagabond, mastery is the valley. The farther Musashi travels down his path, the deeper he sinks into uncertainty, stillness, and self-questioning. He loses the ability to articulate who he is. People ask him, “What style do you use?” and he says, Nothing. No name. No school. He’s left that all behind because naming a style is already creating separation. And the sword, like life, doesn’t care for such divisions.

In fact, Vagabond aligns more with the philosophy of Laozi than with any Western swordsman mythology. Laozi writes in the Tao Te Ching:

“The sage does not accumulate. The more he helps others, the more he benefits himself. The more he gives to others, the more he gets.”

Musashi's path bends in this direction, toward emptiness.

The Sword as a Path of “Unknowing”

To reach this level of insight, Musashi has to unlearn everything he thought mastery was. He has to rid his identity like a snake sheds its skin, many, many times. As he rids, there he reveals something more delicate, painful, and human, but also more genuine.

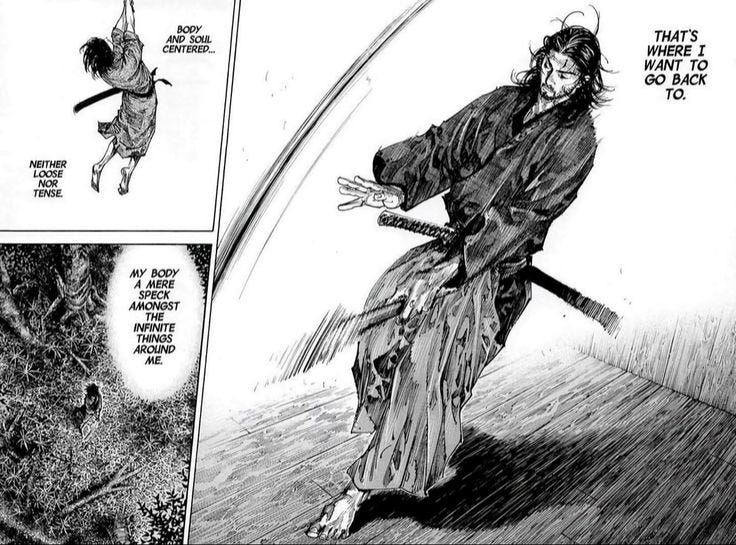

He begins to learn that a man who clings to technique is a man who has not yet understood what the sword is. Technique is a tool. Whereas mastery, the real kind, is an attitude toward the world. It is attention. It is openness. It is the ability to move without being moved by fear, and that can only happen when you simply let go.

This transformation parallels Western existentialist thought as well. In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig describes mastery as a state of Quality, something unnameable, felt in the tempo between mind and matter. Pirsig notes:

“Peace of mind produces right values, right values produce right thoughts, right thoughts produce right actions.”

The more Musashi quiets his mind, the more his sword moves in harmony with what is, rather than what ought to be. So, Vagabond tells us that mastery is a sort of death, a death of illusion, maybe of ego, of the belief that you can ever thoroughly handle life. In the area where illusion dies, something else is born. Clarity.

That is the kind of mastery Vagabond is interested in, and it is surely the hardest to achieve.

Stoicism or Endurance as Revelation

Stoicism, as it pours through Vagabond silently, is not a philosophy of passivity, nor of brute fixedness. It is a philosophy of dignified stillness, clarity under pressure, not mistaking sensation for truth, and facing reality without even flinching. Musashi, whether he knows it or not, walks a Stoic path sculpted from blood, stone, and solitude.

What sets him apart from the warriors he faces is not only physical resilience but also his refusal to seek condolence. After murderous duels, he does not return to a woman’s lap, to wine, to the comfort of narrative like many others do. He returns to the mountain, the soil, and the long hush between inquiries. In this, he unknowingly embodies one of Marcus Aurelius’ most essential maxims:

“You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

(Meditations, VI.8)

Musashi is wounded, starved, hunted, humiliated—and yet, each wound is outlined into discipline. Each lapse is metabolized into reflection. He doesn’t shatter under pressure; he soaks it. The external world becomes a forge, and he is the blade within it.

The Battle Within the Self

True Stoicism is rational engagement with reality. Stoic thinkers, like Epictetus, argued that suffering comes from how we perceive circumstances, rather than circumstances themselves. In Vagabond, this is a transformation we watch unfold in slow, cruel frames.

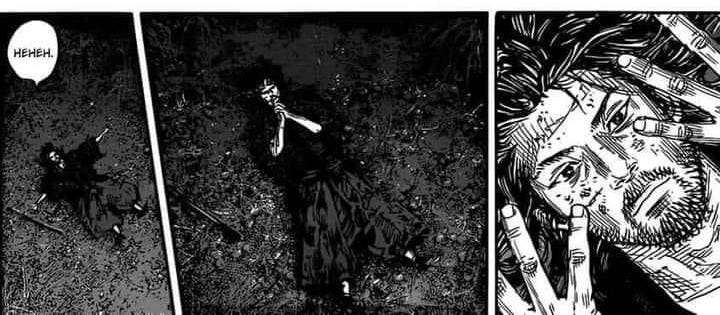

The most precise turning point is Musashi’s recovery and encounter with the farmer’s life. After a desperate, animalistic duel in the Yoshioka arc, a sequence where he kills dozens, nearly dies, and loses almost everything, Musashi finds shelter in humiliation, not heroism. He cannot walk. He can barely move. He steals vegetables from a child’s field. The sword, his pride and identity, is frankly useless.

As opposed to what most people consider, this arc is not filler. It is philosophy generated through mud and rice :) Here, Musashi begins to embody another Stoic insight, this time from Seneca:

“A man is not poor if he has little, only if he desires more.”

He stops thinking in terms of “getting stronger” and begins to observe. The way a child runs. The way water flows. The way plants grow without any instructions. Now these are not martial insights, but, if I may, ethereal ones. In the quiet monotony of rural life, he begins to understand that survival is about balance.

When Reality Hits

Musashi’s transformation is often ugly. He’s dirty. In pain. Hungry. Yet, Inoue’s artistry states these moments with great reverence. Because this is when Musashi begins to see openly. His discipline no longer comes from pride, but from necessity, and eventually, from compassion.

Here, we see a harmony between Zen asceticism and Roman Stoicism. In Zen, enlightenment is earned through silence, simplicity, and sustained attention to the ordinary. Kōans like “Chop wood, carry water” capture the idea that awakening lies in the mundane. Musashi lives this: Every radish he plants becomes an act of philosophy. Every ache in his body becomes a back-and-forth between the self and the world. Even his refusal to return to combat until he has “healed” is about waiting until his soul is ready.

There is a moment, almost indistinguishable, when Musashi stops fighting to prove something and begins being. It reflects Aurelius once more:

“If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it—and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”

(Meditations, VIII.47)

Thus, Musashi’s estimations begin to shift. The world, he notices, does not owe him anything, and this, far from breaking him, frees him.

Solitude, Not Isolation

There is a vital distinction in Vagabond between solitude and isolation. Many of Musashi’s enemies are alone, but not solitary. They are isolated because they are consumed by comparison, shame, or performance. Musashi, in contrast, begins to develop a solitude that fosters. He reads the wind, listens to crows. He speaks to no one for days, and yet, he becomes more human.

In Stoic terms, this is ataraxia—tranquility that is neither giddy nor numb, but clear, grounded. A condition where the soul is not disturbed by external flux. Even when death is imminent, Musashi no longer clings.

Perhaps the most Stoic moment in Vagabond is, surprisingly, a gesture. A tranquil moment when Musashi, alone and tired, places a hand on the earth and smiles. For the first time, he is just present. He does not need a school, nor applause, nor does he need to win.

This, finally, is the Stoic ideal: a man who no longer needs to escape suffering. In the words of Epictetus:

“Freedom is the only worthy goal in life. It is won by disregarding things that lie beyond our control.”

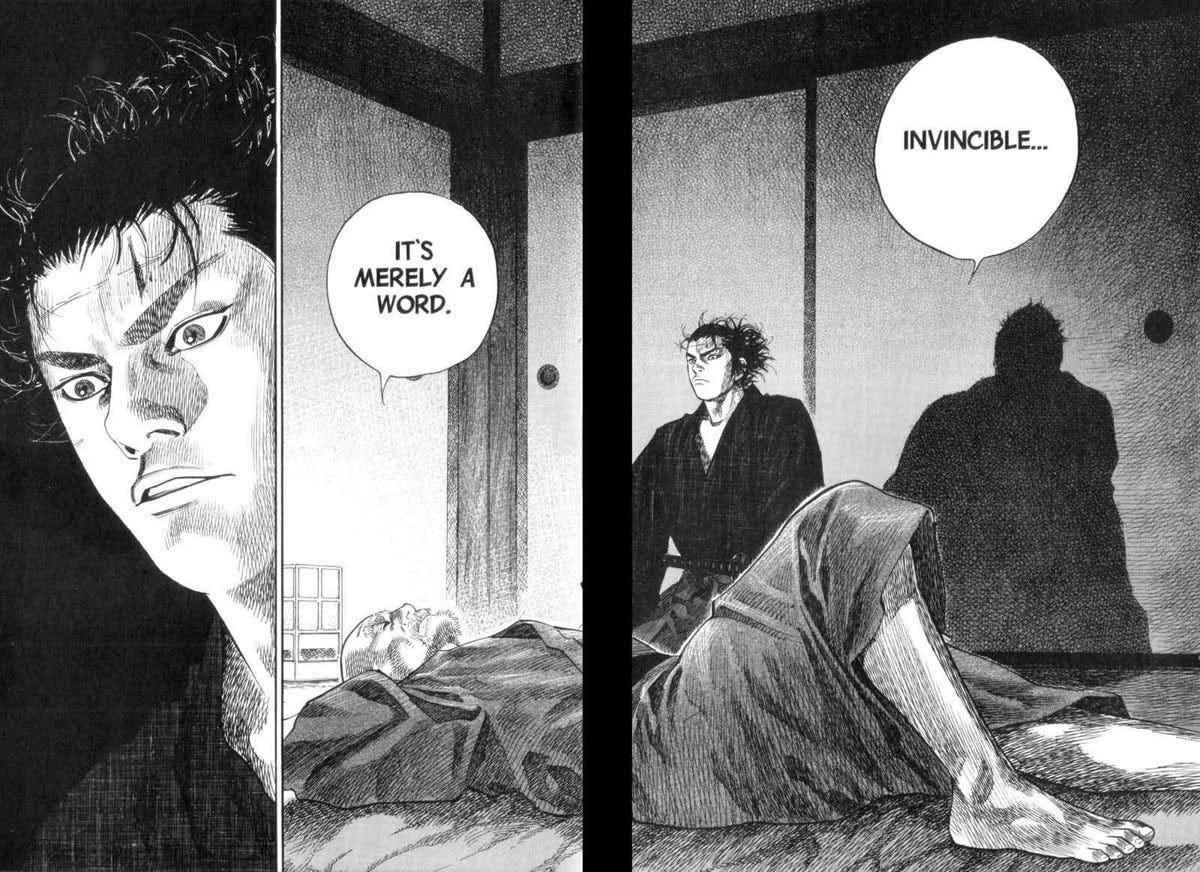

Musashi’s journey, at its core, is about becoming indifferent to invincibility.

From Glory to Grief

The traditional “hero's journey” suggests that meaning lies in becoming something: a ruler, a savior, a champion. However, after dozens of duels, Musashi begins to ask: What am I becoming? Who am I without an enemy?

This echoes Albert Camus’ existentialism, especially in The Myth of Sisyphus. Sisyphus pushes the boulder endlessly uphill, knowing it will fall, knowing it means nothing. Still, Camus conveys, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Why? Because in accepting the absurd, he is free.

Musashi's journey parallels this transformation. The more he chases meaning through violence, the more he confronts the absurdity of that path. The Yoshioka arc is a turning point: he defeats an entire school alone, but instead of triumph, he experiences something closer to grief. He limps away, half-dead, to hide among vegetables and children.

Meaning as Weight

For most of Vagabond, Musashi’s search for meaning is twisted with guilt, legacy, and hunger for identity. But the manga’s later stages pivot. Meaning begins to turn from a goal to be achieved into a burden to be released.

Consider his time with Iori and the villagers. In this phase, Musashi no longer thinks of strength in terms of duels, but in terms of patience, cultivation, and humility. The body that once swung a sword now tills soil. The hand that once trembled from battle now rests on a child’s shoulder. And perhaps the most striking thing: he stops trying to justify himself. This, paradoxically, is when he becomes most complete. He lets go of the story he was trying to write about himself.

This, obviously, reflects Heidegger’s idea of “authentic being”: that we must live with the awareness that death renders all narratives fragile. We must not cling to external roles. We must dwell in time, in place, in silence. And that is what Musashi begins to do.

In Zen, enlightenment is a falling away. When the mind stops grasping, the Way becomes visible. But it was always there.

At last, Musashi’s final transformation is quiet. He learns to be without needing to become, stops asking, and begins seeing.

This is the final paradox of Vagabond: The more you search for meaning, the more it escapes you. The moment you stop searching, you are free. Because you no longer need it. In that freedom, the sword becomes something else entirely: just an object among objects.

Like a rock.

Like a stalk of grain.

Like a man sitting under a tree, breathing, free.

Okay then, it’s time to talk about the technical parts!

Negative Space

In Eastern art, particularly sumi-e (Japanese ink wash painting), what is left untouched is as important as what is drawn. This principle dominates Vagabond. Entire panels are left blank save for a single stroke, a tree limb, a wave in a pond, the side of Musashi’s cheek. The world bleeds away, and we are left suspended in a void of quiet presence. This is emptiness as fullness—a ma (間), the Japanese concept of meaningful interval, like the silence between notes in music. In Vagabond, this space is philosophical. It invites the reader to see, not just look.

Texture and Gesture

Inoue’s line work is a study in tension. Faces are crosshatched. Sweat streaks, drips, and accumulates. Battle is wholly emitted. But it is in the quiet panels where his genius lies, because in Vagabond, texture is psychology.

For instance, when Musashi limps from the Yoshioka slaughter, the page is smeared. Each panel is scarred like his body. When he farms radishes, the ink softens. As you see, even his brushstrokes obey his philosophy: aggression hardens the world; attention softens it. The panels really just breathe. This visual modulation reflects, again, Zen calligraphy, where the stroke exposes the state of mind of the practitioner. Inoue renders every stroke this way.

Composition from War Scroll to Sutra

Vagabond’s large panels resemble emakimono, Japanese picture scrolls read right-to-left in long, continuous motion. Inoue often composes scenes as if the page is, as I’ve stated above, a breathing landscape. This de-centering draws attention away from the character’s ego and toward the whole field of being. The sword may enter from the left, but the mountain holds the page. A man dies in the lower corner, but the sky extends above.

Additionally, in some frames, all perspective vanishes. There is no horizon or background. Just ink and void.

These moments also mirror Zen ink paintings of Daruma or Bodhidharma, figures generated with wild, minimal brushstrokes in the center of unpainted paper. The unpainted area becomes the infinite—Mu, the void that contains all things. Musashi’s final philosophical frames float in this space.

The Absence of Victory

Even in combat, where most manga burst with spectacle, Inoue uses control. The final blow is rarely shown. We see the before, or the after, but the killing is often off-frame. He refuses to glorify technique because the real fight was never between swords. It was within silence.

The result? A comic that moves at the coherence of breath rather than the speed of the plot.

If you enjoyed this post and wish to show gratitude, you may do so by making a donation starting at just $5 via the link below. Your kindness helps me continue my studies and pursue my profession—thank you.

Fantastic stuff.

Thanks for treating comics (manga) with respect.

A magnificent, quiet essay. The writer has understood something.