Historical Linguistics: How Ancient Languages Shape Modern Thought 0.4

Third Episode: Classical Chinese, Classical Tibetan & Old Burmese

When we turn our gaze eastward, beyond the Mediterranean, beyond the foothills of Persia and the banks of the Indus, we face a different structure of thought and language. Where Latin and Greek framed rationality through abstraction and formal logic, the languages of East and Central Asia offered an entirely different linguistic infrastructure: one grounded in relationality, cosmological harmony, and inner liberation. Classical Chinese, Classical Tibetan, and Old Burmese, each an intellectual and cultural cosmos, did not just convey information; they structured reality. Their grammars were, in a way, grammars that shaped our world.

Classical Chinese (Sinitic)

The Language of Order & Dao

Classical Chinese (文言文 wényánwén) is less a “language” in the modern, spoken sense than a system of ideographic condensation, stripped of inflection, bereft of open grammatical indicators, yet extraordinarily rich in philosophical subtlety. It is perhaps the purest manifestation of the idea that brevity is not the enemy of complexity but its very form.

Unlike inflectional Indo-European languages, Classical Chinese relies heavily on word order, context, and semantic pairing rather than grammatical morphology. There are no verb conjugations, no noun declensions. This led to an interpretive directness that mirrors the Daoist principle of wu wei (無為)—non-intervention, or action in accordance with nature. In a very real sense, the grammar of Classical Chinese invites the reader to perform the act of interpretation, to engage in a dialogue with the text. The Confucian Analects, for instance, read not like a monograph but like a series of aphorisms, layered with ambiguity and cultural reference.

The result is a language that cultivates attention, that requires a slow and reflective approach. There is no passive voice in Classical Chinese; agency is assumed. Subjects may disappear, but their effects walk through the line. The omission itself becomes meaning.

Each Chinese character is a semantic image, a combination of phonetic and radical components that point not just to meaning but to cosmological position. Consider the character for Dao (道): a combination of the radicals for "walk" (⻌) and "head" (首), implying both a physical path and the leading principle. Language here is not dictatorial, it is cosmically uniting.

The structure of Confucian ethics, the Daoist metaphysics of balance, even the bureaucratic principles of the imperial state, all found in Sinitic, a medium that not only recorded but also embodied them.

A Few Fun Facts:

— In Classical Chinese, a single character can form an entire sentence. Example: 行 (xíng) can mean “He walks” or “To walk,” depending on context. That’s ultra-minimalism right here.

— There are no tenses. Time is implied, not told. Classical Chinese has no verb conjugation, so “I eat” and “I ate” can be the same sentence; context does all the work.

— Chinese social media regularly uses chéngyǔ (four-character idioms) from Confucius or Zhuangzi. They’re meme-ready: short, profound, and punchy.

— Some Chinese characters are pictograms, visual representations of their meanings: 木 (tree), 日 (sun), 山 (mountain). Ancient Unicode = Ancestors of the modern-day emojis.

Classical Tibetan (Tibetic)

The Grammar of Liberation

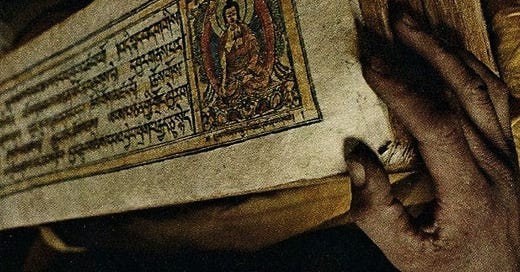

Classical Tibetan (Chos skad, “religious language”) emerged as the vehicle for a spiritual revolution. Transformed from a vernacular into a sophisticated scholastic language by the needs of translating the Sanskrit Buddhist canon, Classical Tibetan became a linguistic bridge between India and the Tibetan plateau, reshaping the Tibetan mind in the image of both logical precision and mystical clarity.

Grammatically, Classical Tibetan is an “ergative” language, which means that the subject of a transitive verb is marked differently than that of an intransitive one, a structural distinction that mirrors the philosophical concern with intentionality and karmic reason. The very construction of the sentence encodes moral responsibility.

The influence of Indian logic (pramāṇa) transformed Tibetan into a vehicle of philosophical dissection. The works of Dharmakīrti and Dignāga were translated into Tibetan with exceptional precision, necessitating the development of a rich scholastic vocabulary and syntactic accuracy. Debaters in monastic universities such as Sera and Drepung would analyze arguments not just with logical rigor, but with grammatical precision rooted in the language's structure.

Its orthography also preserves archaic consonants no longer pronounced in the spoken language, ghosts of its phonological past. This fossilization is not accidental. It reflects a cultural conservatism: the written form is not to follow speech, but to capture it. It is an act of memory against impermanence, of stability against the flux, deeply Buddhist in essence.

And yet, it is also an, if I may, emancipatory script. The writing system became the container for the Kangyur and Tengyur: the Tibetan Buddhist canon. To write in Tibetic was to write on the origins of samsara and nirvana alike.

A Few Fun Facts:

— In monastic debate, every time a monk makes a point, they clap their hands forcefully toward the opponent. It’s dramatic, rhythmic, and deeply logical.

— The verb bsgom means "to meditate," but Tibetan grammar has specific forms to indicate what kind of meditation, such as on shunyata (emptiness). Try conjugating "I used to meditate emptily before lunch" in English. It is harder than you’d imagine.

— Due to agglutinative suffixes, Tibetan can pack multiple grammatical elements into one word, like German, but more mystically.

— Up to 60% of Classical Tibetan’s philosophical vocabulary is borrowed from Sanskrit, but restructured into Tibetan syntax. It's like Plato retranslated through Homer and wrapped in a Himalayan shawl.

Old Burmese (Sino-Tibetan)

Language of Kings and the Dharma of Earth

Old Burmese, emerging in the 11th-century Pagan Kingdom, is the linguistic root of modern Burmese. As a Tibeto-Burman language, it shares much with Tibetan in its syntactic structure, but was shaped in equal measure by Pali, the language of Theravāda Buddhism.

Old Burmese was written in the Brahmi-derived Burmese script, itself adapted from Mon, which was in turn influenced by South Indian scripts. The result is a visual and linguistic re-inscription: every curve of the script is a meeting point of kingdoms and philosophies. The language was phonetic, syllabic, and structurally analytic, favoring word order over inflection, yet drawing heavily on Pali compounds and Sanskritisms to express abstract ideas.

It served two distinct but related functions: royal administration and religious information. For instance, in one context, it cataloged the actions of kings and the laying of irrigation systems. In the other, it carried the dhamma across plains and temples, carved into stone and palm-leaf manuscripts.

It had an emerging tonal system, unusual for the time and typologically rare in written languages of antiquity. This tonal evolution would later define modern Burmese, but even in its early form, tone functioned not just to distinguish words but to create a poetic rhythm that resonated with the chants of monks and the meter of royal orders.

The verbs followed postpositional particles, telling relationality and hierarchy in a way that aligned perfectly with the Theravādan ethical universe. Time and action were not absolute; they were relative to intention, status, and worth.

A Few Fun Facts:

— The first known use of Old Burmese is a real estate deed. The Myazedi Inscription (1113 AD) records a prince donating land and slaves to a temple. That's the Burmese Rosetta Stone, and it’s about property rights.

— Old Burmese was multilingual. The same stone inscription often appears in Pali, Sanskrit, Mon, and Burmese, a medieval Southeast Asian Google Translate monument.

— The rounded script style was developed for writing on palm leaves, as straight lines would tear the leaf. The tradition stuck, even when ink replaced palm.

— Rebus-like metaphors appear in early Burmese verse. A “banana tree” could mean "mother," because bananas grow in clusters and die after fruiting. Sweet and sad.

An Eastern Model of Intellectual Inheritance

Where Latin and Greek taught the West to divide the world into categories (substance, attribute, genus, and species), the languages of the Sino-Tibetan world taught their speakers to relate to the world: to outline its changes, harmonize with its patterns, and pursue release from its illusions.

In linguistic terms, Classical Chinese (Sinitic) prioritizes minimalism, semantic density, and heavenly order. Classical Tibetan (Tibetic) emphasizes rational substructure, syntactic flexibility, and moral grammar. Old Burmese harmonizes administrative clarity with religious rhythm, preserving cultural identity through phonetic innovation. Each of these languages did not simply describe a world, they literally shaped it.

In the following episodes of this series, I’ll share Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, and Akkadian with you. As Egyptian is not a Semitic language, we have to leave it to the side for a while. If you enjoyed this post and wish to show gratitude, you may do so by making a donation starting at just $5 via the link below. Your kindness helps me continue my studies and pursue my profession—thank you.

What a brilliant introduction to the psychological roots of language - the incorporation of environment, ritual, of physical limitations and the exploding stars of theory.