Permit me a rather bizarre confession: I always wanted to be Indiana Jones.

Not the man, not the gun-slinging, wise-cracking American caricature. I have no desire to brawl in a Cairo bazaar or swing, vine-like, from moving trucks. What I always wanted was more fundamental. It is the idea. The life that dares to make knowledge a compass, a way through the viscous moral and material jungle of the “modern” world.

You may scoff. But pause. Look deeper. This strange-looking longing is not mine alone; it lives, subtly, in many of us who were raised among books and buried in theory, who speak dead languages fluently but have never or rarely touched a ruin. For those of us who wander the catacombs of history with only paper and ink, there is something almost unbearable about the distance between what we know and what we can experience. Indiana Jones is, perhaps, a dream that this crack can be crossed. That we might yet touch what we’ve only read. That we might become what we’ve only envisioned, free.

In truth, the fantasy is not about action. It is about escape from paralysis, from the devoid corridors of academia, from the pixelated neuroses of a modern world that consumes meaning faster than it can create it. It is about freedom. To be lost in a jungle and know precisely what the temple inscription means. To walk into darkness and not feel fear, but purpose. To reveal the ancient and serve as its voice in a world that has forgotten how to listen.

I, for one, am tired of spectating. And if you are honest with yourself, you might be too.

So this essay is not exactly about me or him. It is about you and all of us. Maybe you are also, unconsciously, waiting for a whip to be placed in your hand and a map to be unrolled before you.

If so, you’re not alone.

The Intellectual Ache

Listen closely. There exists within you a persistent and growing psychic dissonance, a dichotomy between your internal world of knowledge and the external world in which you are expected to live. In clinical terms, one might call it a presentation of epistemic alienation: the state in which one’s accumulated knowledge becomes psychologically static, cut off from meaningful engagement with reality. We do not suffer from ignorance, we suffer from an excess of untethered understanding. And as Viktor Frankl argued, “When a person can’t find a deep sense of meaning, they distract themselves with pleasure.” But what happens when even pleasure feels dull besides the magnificence of ancient truths that remain unknown to us?

This is where the discomfort begins. It is not emotional but ontological. For instance, my sense of being feels incomplete all the time, as if my intellect is suspended in stereotype, unable to root itself in the physical, historical, or experiential world. I am able to translate the vocabulary that few around me can hardly pronounce. I understand the funerary stelae of long-dead empires. I know the structures of languages that are no longer spoken by human tongues. But I have not touched them. I have barely even stood where they stood. And this is, in effect, a psychological fragmentation of self.

According to Carl Jung, the human psyche seeks integration—a cooperation between the unconscious and the conscious, the symbolic and the literal, the inner and the outer. My unconscious has long been occupied by archetypes of the seeker, the scholar, the hero. But modern life offers few roles in which these archetypes may fully express themselves. The result is what Jungians would call a failure of individuation: our potential self remains shapeless because the modern world denies it the conditions under which it might appear.

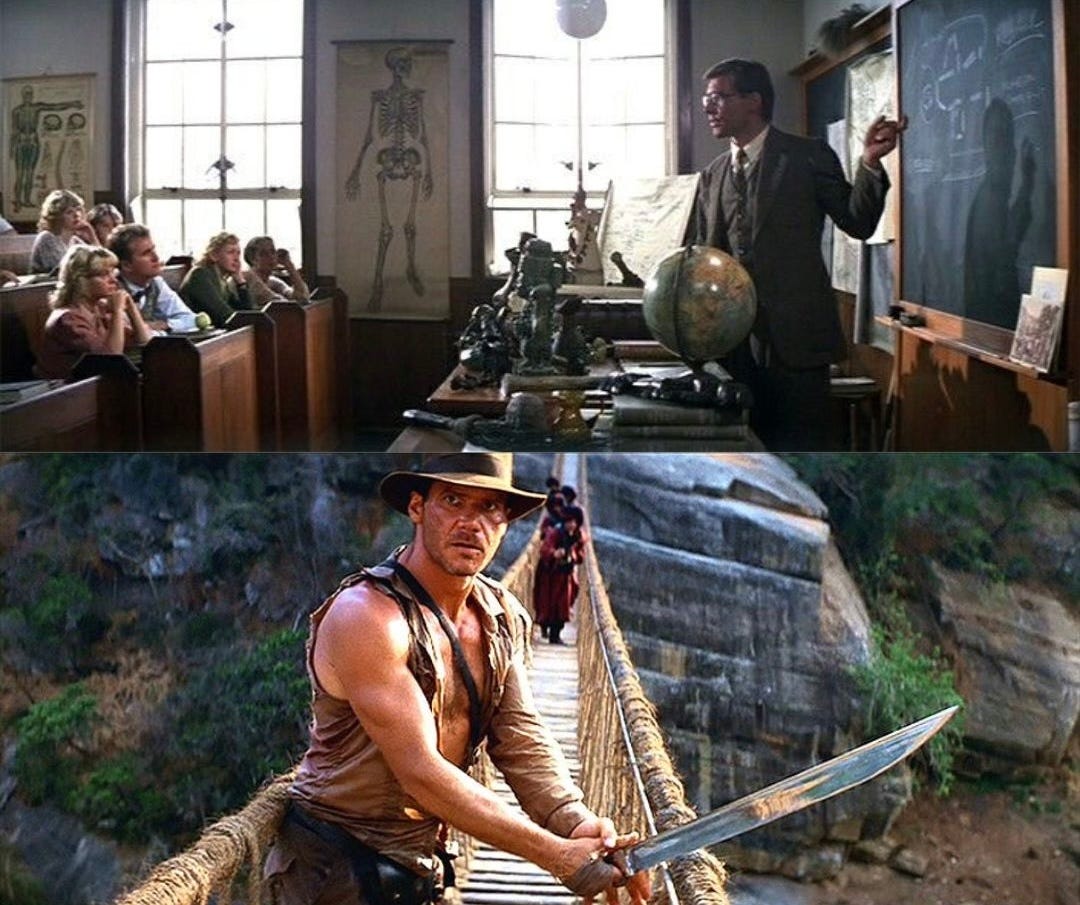

And so, Indiana Jones. Not as fantasy, but as an archetypal equalizer. He is the symbolic synthesis of what I am and what I am denied the chance to become. In Jungian terms, he is an animus projection—a figure that carries both the shadow and the ideal, representing an integrated self: the intellectual who acts, the academic who dares, the man of theory who also bleeds. He is not a wish for excitement; he is a symbol through which all of our psyches seek repair.

In Freudian terms, one might say we are driven by the reality principle while secretly starving for the pleasure principle, but a pleasure of a very unconventional kind: contact. Our drive is not eros in the passionate sense, but in the Platonic sense—the yearning of the soul to return to what it once knew. That is why ruins call to us. That is why books are no longer enough.

So, Mr. Jones is not the solution but the outline of the solution. He is the unconscious mind’s way of asking:

What if knowing wasn’t the end of meaning, but its beginning?

The Call to Adventure (Danger, purpose, and the restoration of the self.)

There is, within you, an unspoken yearning for fracture, for some event, real or symbolic, that might take you away from the stasis of modernity and call you toward something larger, older, and more dangerous. In the language of Joseph Campbell, this is the call to adventure, the mythic warrant that draws the psyche away from the known world and into the realm where transformation becomes likely. Books are their voice. Studies, their shadow.

This desire, at its core, though mostly taken wrong for adrenaline or exoticism, is about meaning. In existential psychology, meaning is something earned through risk. Viktor Frankl considered that meaning is often found through suffering; that purpose is generated. And modern life, for all its comforts, refuses us that struggle. It has anesthetized risk, neutered curiosity, and bureaucratized danger. We do not suffer in the noble sense; we simply decay in the ordinary one.

At this point, Mr. Jones, to me, is not a thrill-seeker. He is a human being plagued by the necessity of purpose. He chooses trouble because it is the only condition under which clarity becomes possible. When you stand between life and death, every action is soaked with meaning. Every breath matters. This is, in psychoanalytic terms, a confrontation with the real—the Lacanian réel—that which cannot be symbolized, negotiated, or fully understood. And for many of us, myself included, modernity has become too symbolic, too distanced, too safe.

So you do not crave danger out of some juvenile thirst for drama. You crave it because danger interrupts numbness. Because mystery disassembles the cynical ego. Because in the unknown, you might finally become awake.

From a trauma-theoretic perspective, this makes a kind of inverse sense. The modern subject, particularly the intellectual one, suffers from a form of low-grade, ambient trauma—a chronic dissociation from illustrated life. We are not hurt, exactly; we are alienated. I sit with texts that speak of gods and tyrants and revolutions and rituals, and yet, in my world, I am expected to write calmly, footnote carefully, and behave professionally. It is a form of psychic partition.

So yes, you want the danger for its unification. Because in facing it, you might gather the scattered parts of yourself—the scholar, the child, the idealist, the one who once read about Atlantis by flashlight and believed it could still be found!

The Myth of Freedom (Escaping modernity and reclaiming the wild self.)

Erich Fromm, in his Escape from Freedom, argues that the modern individual, far from being liberated, suffers under a new tyranny: the burden of choice without purpose. We are free to do anything, except matter. We have abandoned the certainties of tradition and myth, but built no new cathedral to stand in their place. What remains is anxiety, dressed up as independence.

This is a freedom I reject. The freedom of market identities, algorithmic passions, and curated relevance. My soul, if we may still use that word, does not respond to that kind of independence. It craves not for choice, but for belonging. And belonging, I believe, is most purely felt in nature. In the unowned world.

Indiana Jones, for all his faults, belongs to that world. He lives by the desert’s logic. He decodes languages and geographies. Of course, he is not free in the legal or political sense, he is just untamed. He is the civilized man who remembered his primal self and returned to it with affection. He is proof that intellect and instinct need not be enemies.

From a Jungian standpoint, this is the reintegration of the primitive self, the archaic archetypes buried underneath modern ego structures. Our institutions prize rationality, but the unconscious speaks in stone and vision. By chasing ancient ruins, by diving into catacombs, Jones reclaims the parts of himself our world has concealed. In him we see the lost ritual of becoming. The journey away from anesthesia and toward wild integration. The refusal to live as a series of roles and the audacity to live as a myth.

To walk not through history, but into it.

I see myself in that gesture. Rousseau, too, believed that civilization corrupts by isolating us from nature, from community, and most tragically, from ourselves. And to be clear, I do not want to escape modernity because I hate it. I want to escape it because it has no place for what I am becoming. Perhaps you do too.

The Ruin and the Self (Why we want to excavate the past to understand ourselves.)

No one tells you, when you begin to study ancient things, that you are also studying yourself. They tell you history is a map of facts, a heritage of wars and rulers, though that is a deflection. What they never admit, most probably because they fear it, is that the ruin belongs to you. Every temple cracked by time is also a portrait of your own fragmented psyche, and every inscription faded by centuries mimics the slow weakening of meaning in your life.

This is what drives me toward antiquity. A kind of psychic necessity. In psychoanalytic terms, it is a return to the primal scene of origin. Jung called this the collective unconscious—an extensive psychic inheritance that ties us across time, across cultures, across the thin illusion of modern separateness. When I translate the last words of a dying king, I feel like a descendant. I feel like I am reclaiming something that was always mine.

Indiana Jones, again, besides being a professor or adventurer, is a psychopomp—a guide between the worlds. I suspect the reason so many people unconsciously identify with him is because he performs a task we all secretly crave: the excavation of the buried self.

We are born into systems, not myths. We are told to build futures, not to understand our past. But one who can not understand their past, can not build their future.

In an ontological reassembly, a moment in which the self, so often fragmented by digital speed and academic conception, becomes whole again. Indiana Jones, for all his flaws and pulp-fiction flair, embodies impulse in its clearest form: the belief that truth, buried though it may be, still exists, and that we must dare to dig for it.

If you enjoyed this post and wish to show gratitude, you may do so by making a donation starting at just $5 via the link below. Your kindness helps me continue my studies and pursue my profession—thank you.

Wonderful essay, really enjoyed reading it!

“..pixelated neuroses of a modern world that consumes meaning faster than it can create it.” ♥️